Reimagining Patient-Centered Care During a Pandemic in a Digital World: A Focus on Building Trust for Healing

The National Academies are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The National Academies are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Visit our resource center >>

COVID-19 has redefined the patient-provider experience. Panicked patients now struggle in solitude to deal with the mental and physical ramifications of COVID-19, while overworked, under-resourced, and exhausted care providers deliver treatment at a distance to minimize the risk of viral transmission [1]. With over 30 million cases and over 500,000 deaths due to COVID-19 in the United States alone, the fear and anxiety experienced by both patients and providers is understandable. What further complicates an already difficult situation is the forced and necessary isolation to limit the spread of disease. Physical distancing has shifted COVID-19 from a difficult illness to a tragedy, especially for patients who lack the ability to connect with loved ones virtually. In those cases, care providers may feel they must fill the void left by the absence of family members, but even care providers must limit their time with patients because of the contagious virus, further restricting patient-provider bonding, trust formation, and the healing power of touch.

While some COVID-19-related restrictions will be lifted after the pandemic subsides, physical distancing, with greater reliance on technology for connecting with patients, will most likely be a lasting change. Providers are speaking with and seeing patients in ways reflective of this new, generally more efficient health care environment, but are they able to recreate the provider-patient trusting relationship reminiscent of in-person bonding? Creating a trusting bond with patients is an essential part of healing relationships [2], and empathy is key to building patient-provider trust. However, showing empathy through digital tools is often challenging. But like all the challenges facing health care workers during the pandemic, care providers are learning how to show empathy and gain their patients’ trust using technology as a tool rather than an impediment to touch. Transferring these skills to students

and trainees will help them navigate the new digital caring environment that is certain to remain even after the pandemic.

Training Health Professionals from Distanced Education to Practice

Without a playbook to rely upon, Millstein and Kindt [3] drew ideas from pre-pandemic surveys to help clinicians make adjustments to their practices in light of COVID-19 and the need for more online and physically distanced patient encounters. The authors’ guidance emphasized establishing a trusting relationship between caregiver and patient through active listening, empathic communication, and not appearing rushed. Providers will need to constantly assess their online presence in asking whether I projected empathy and expressed welcoming body language and facial expressions that says to the patient, “I am here for you.” Educators and practitioners who role model self-assessment for learners can help students and trainees realize the significance of assessing oneself as a caring provider.

Empathy for Gaining Trust

All learners, from prelicensure to practicing professionals, need to recognize the importance of empathy for gaining patient trust. By conveying warmth and knowledge, care providers can overcome challenges with physical distancing and online interactions, and build trust with their patients. Terry and Cain offered educational modalities for teaching empathy to future care providers [4] that include roleplaying patient-provider interactions with peers and engaging in self-reflection exercises with mindfulness training. Recording online roleplaying interactions can be useful for educational purposes and can help learners pay particular attention to assessing facial expressions for picking up nonverbal cues. Asking the person roleplaying the patient to mumble while wearing a mask over the nose and mouth can give learners a deeper appreciation for the challenges faced by hearing-impaired patients.

Digital Touch

A gentle touch in a time of need has been described as reassuring, comforting, and soothing, with the potential for suppressing pain and other negative feelings [5]. The key to cultivating trust via digital platforms is to recreate the pleasurable neurological response to a physical gentle touch—a so-called “digital touch.” Research to date has not focused on the virtual environment thereby opening opportunities for learners to participate in research activities aimed at identifying ways to digitally touch patients. In collaboration with providers and educators, students could test innovations and report on their findings. Such efforts could potentially improve future online health care interactions particularly with stressed and anxious patients. The studies might include virtual verbal empathy in combination with other relaxation techniques like playing soft background music at the start of a consultation [6], engaging patients in gentle stretching and breathing exercises [7], instructing patients to generate aromas that conjure up positive autobiographical memories during the online appointments [8], asking patients to stroke a pet during the patient-provider interaction [9], or using humor [10] to ease anxiety during tense, online interactions. Whether online relaxation methods like these can simulate the neurological response to a gentle touch is unknown and could be explored with thorough student-led research projects.

Digital Trust

The term digital trust, when used by the technology sector, describes issues of privacy in using data [11]. This same perspective applies to the health sector, although one could argue its application to telehealth goes beyond data privacy. When students are learning how to provide care in the virtual environment, it is helpful for them to view telehealth as a complex network of digital trust touchpoints that go beyond confidence in the safety and privacy of the technology. Technology use in the health sector also involves establishing a trusting relationship in which providers keep patients’ health and well-being at the center of their care, even though financial impacts are always a consideration. Providers risk losing patient trust if health does not remain a focus.

Trust between a patient and provider is gained over time. Conveying this message to learners may be helpful with the caveat that it is not yet known whether a projected screen image or phone call can garner the same level of trust as an in-person visit. It may be that digital trust is influenced by generational exposure to technology. For example, millennials, who represent the first generation to have grown up with the internet, appear to have greater trust in the digital world than other generations [12]. Giving health professional learners assignments exploring digital trust stratified by age may be a useful exercise. Other projects could involve exploring key components of developing a trusting relationship such as understanding the importance of demonstrating empathy and compassion and how each differs from sympathy [13].

Navigating a New and More Digital Caring Environment

COVID-19 has accelerated the pace toward blended care, where patient interactions are shifting to a predominantly virtual or telecommunication platform. For example, a COVID-19-inspired innovation involved attaching cameras to IV poles in hospital rooms, which allowed doctors and other care providers to communicate with patients more quickly and from a distance [14]. Doing so increased efficiency and limited exposure to COVID-19. However, the solely digital presence of caregivers even within a hospital could have unintended consequences by further isolating patients. This further isolation could potentially have devastating consequences given the high rates of anxiety (92 percent of 50 respondents), worry (96 percent), and feelings of isolation (90 percent) reported by patients admitted to a COVID-19 hospital ward [15]. Care providers should reach out to mental and behavioral specialists to help think through potential psychological ramifications of embracing such innovations as routine within hospitals.

The goal of the new, blended health system is to create a digital “caring” environment while embracing new technology and innovations. Doing so will require redefining who the members of the care team are and considering whether the technology itself is part of the team or if it is an enabling factor for effectively connecting the team members. For many, the health care experience starts with an online search or a phone call to the institution inquiring about health care-related services. What was the patient’s experience? Has the website been updated with the latest information, and do the hyperlinks work? Was the person who answered the phone trained to remain calm, show respect, and demonstrate competency in easing worries of an anxious caller? Often, this call or internet search will be the first interaction between the team and its patients. Carefully orchestrating the technology-enabled experience can reduce anxieties and limit patients’ frustrations. After the patient gains access to the health care system, questions turn to provider coordination and displays of empathy for building trust. How well did the care providers coordinate throughout the virtual experience for the patient? Were there smooth transitions from one care provider to the next? Were the providers trained to express digital empathy and create a digital trusting patient-provider relationship?

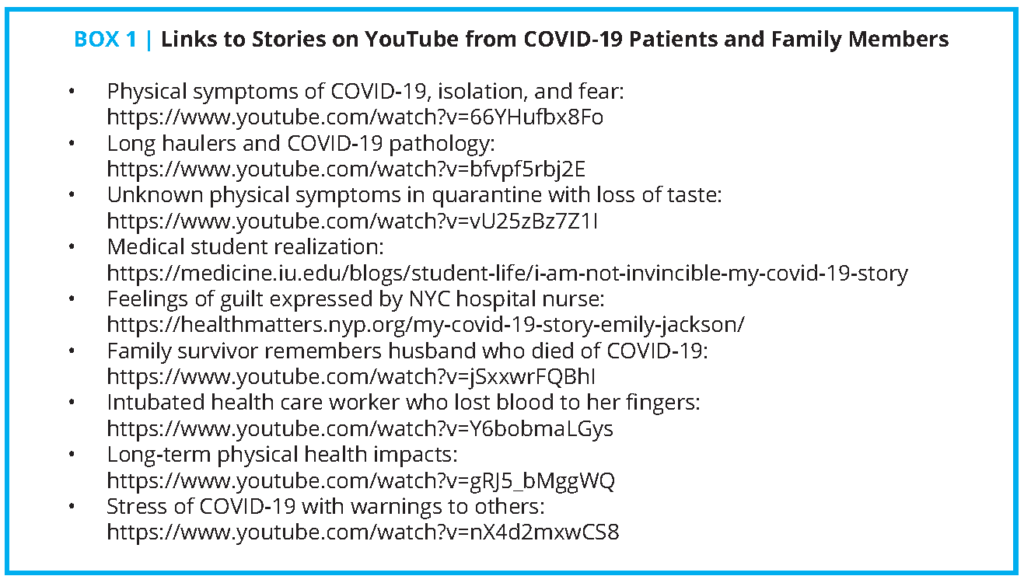

Making use of health professional students to map and assess the entire patient experience can be a valuable assignment, particularly if learners are tasked to work on interprofessional student teams guided by a mix of care providers. The students could assess how effectively different professions worked together in the virtual environment to the benefit of the patient. Learners could also explore digital touch points where interprofessional providers could easily share information, possibly across virtual platforms that could, for example, bring dentistry into a virtual connection with medicine, nutrition, and mental health counselors. In this way, learners and patients are integrated into the new care environment as key members of the digital care team. Prior to initiating the mapping exercise, educators might require students to conduct background research on YouTube that entails locating, viewing, and sharing with interprofessional classmates the video-recorded stories of COVID-19 patients and families (see Box 1). The activity could help students gain a deeper appreciation for the range of mental and physical health challenges faced by COVID-19 patients, how different professions interpret and would act upon patients’ self-described symptoms, and how a team could work collaboratively with the patient.

Call to Action

The need for physical distancing required by the pandemic and the limits of provider training create a visible tension requiring an immediate call to action for all health professionals to create a renewed patient-provider trust relationship within a digital world. To accomplish this, providers and educators should test models for humanizing physically distanced care and education. Whether the interaction is through a mask, a phone, or online, exploring methods of offering emotional support to patients, learners, and colleagues must be reported for there to be a shared mental model of best practices for creating trusted digital relationships. Educators and care providers should make the best use of their learners to map the physical and virtual environment to determine who makes up their sphere of influence and how well the experience is patient-centered. Once outlined, it will be important to understand the critical role each person has in supporting the patient as well as each other during one of the most challenging times in modern history. The key will be to create digital empathy and compassion for gaining digital trust for maximal healing of the mind and the body of patients, learners, health professionals, and the entire care team.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! #COVID19 has redefined the patient-provider experience, and creating digital empathy and compassion will be key for gaining patient trust, according to authors of a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202105c

Tweet this! #COVID19 has redefined the patient-provider experience, and creating digital empathy and compassion will be key for gaining patient trust, according to authors of a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202105c

![]() Tweet this! The authors of our newest #NAMPerspectives commentary discuss how the need for physical distancing and limits on provider training during #COVID19 require a renewed patient-provider trust relationship within a digital world: https://doi.org/10.31478/202105c

Tweet this! The authors of our newest #NAMPerspectives commentary discuss how the need for physical distancing and limits on provider training during #COVID19 require a renewed patient-provider trust relationship within a digital world: https://doi.org/10.31478/202105c

![]() Tweet this! The goal of a health system that blends digital and in-person visits, like arose during #COVID19, is to create a digital “caring” environment while embracing new technology and innovations. Read about a potential path forward in #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202105c

Tweet this! The goal of a health system that blends digital and in-person visits, like arose during #COVID19, is to create a digital “caring” environment while embracing new technology and innovations. Read about a potential path forward in #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202105c

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Vais, S. 2021. The Inequity of Isolation. New England Journal of Medicine 384: 690-691. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2029725.

- Scott, J. G., D. Cohen, B. Dicicco-Bloom, W. L. Miller, K. C. Stange, and B. F. Crabtree. 2008. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 6(4): 315-322. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.860.

- Millstein, J. H. and S. Kindt. 2020. Reimagining the Patient Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. NEJM Catalyst. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7371288/ (accessed May 21, 2021).

- Terry, C. and J. Cain. 2016. The Emerging Issue of Digital Empathy. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 80(4): 58. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe80458.

- Ellingsen, D.-M., S. Leknes, G. Løseth, J. Wessberg, and H. Olausson. 2016. The Neurobiology Shaping Affective Touch: Expectation, Motivation, and Meaning in the Multisensory Context. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1986. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01986.

- Jasemi, M., S. Aazami, and R. E. Zabihi. 2016. The Effects of Music Therapy on Anxiety and Depression of Cancer Patients. Indian Journal of Palliative Care 22(4): 455-458. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5072238/ (accessed April 12, 2021).

- Zaccaro, A., A. Piarulli, M. Laurino, E. Garbella, D. Menicucci, B. Neri, and A. Gemignani. 2018. How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 12: 353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353.

- Herz, R. S. 2016. The Role of Odor-Evoked Memory in Psychological and Physiological Health. Brain Sciences 6(3): 22. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5039451/ (accessed April 12, 2021).

- Shiloh, S., G. Sorek, and J. Terkel. 2010. Reduction of State-Anxiety by Petting Animals in a Controlled Laboratory Experiment. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 16(4): 387-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061580031000091582.

- Menéndez-Aller, Á., Á. Postigo, P. Montes-Álvarez, F. J. González-Primo, and E. García-Cueto. 2020. Humor as a protective factor against anxiety and depression. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 20(1): 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2019.12.002.

- IBM. n.d. Building digital trust into better experiences. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/security/digital-assets/digital-trust-ebook/ (accessed April 12, 2021).

- Alkire, L., G. E. O’Connor, S. Myrden, and S. Köcher. 2020. Patient experience in the digital age: An investigation into the effect of generational cohorts. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 57: 102221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102221.

- Sinclair, S., K. Beamer, T. F. Hack, S. McClement, S. R. Bouchal, H. M. Chochinov, and N. A. Hagan. 2016. Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: A grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliative Medicine 31(5): 437-447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316663499.

- Hayhurst, C. 2021. Hospitals’ In-Room Cameras Enable Seamless Visits and Better Safety. Health-Tech, January 21. Available at: https://healthtechmagazine.net/article/2021/01/hospitals-room-cameras-enable-seamless-visits-and-better-safety (accessed April 12, 2021).

- Sahoo, S., A. Mehra, D. Dua, V. Suri, P. Malhotra, L. N. Yaddanapudi, G. D. Puri, and S. Grover. 2020. Psychological experience of patients admitted with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 54: 102355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102355.