A Call to Strengthen Mental Health Supports for Refugee Children and Youth

A refugee is someone who has fled from his or her home country and cannot return because he or she has a well-founded fear of persecution based on religion, race, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.

“Refugee Admissions,” U.S. Department of State [1]

The United States thrives due to the strength, determination, diversity, and innovations of refugee populations. Yet resettlement policies do not align with the needs of refugees entering the United States, especially those of children and youth who have experienced trauma in their countries of origin or during the process of seeking asylum. It is important that the fields of health, education, and social welfare develop policies and practices to meet the needs of refugee children and youth—and their families—so that they can become strong, healthy, and educated citizens who contribute to the prosperous future of the United States.

Background

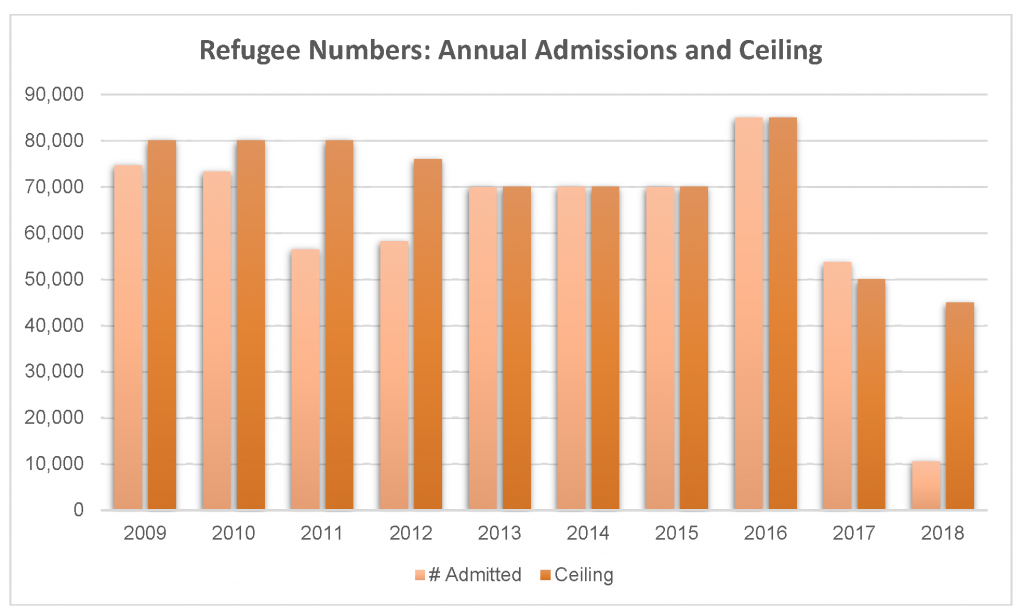

The United States has an extensive history of providing resettlement opportunities to thousands of families worldwide who are fleeing political turmoil, religious persecution, and chronic violence in their home countries. Since 1975, the United States has taken in over 3 million refugees. The number of refugees admitted each year fluctuates, depending on the political instability around the world as well as the political climate and national priorities of the United States (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Refugee Numbers

SOURCE: US Department of State. n.d. Refugee admission statistics. https://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/statistics/ (accessed June 28, 2018).

NOTE: US refugee admissions and ceiling numbers as of March 31, 2018.

Bridging Refugee Youth & Children’s Services, a national technical assistance program supporting refugee families, stated that nearly 40 percent of refugees who resettle in the US are children. While many refugee children resettle with their parents, nearly 200 each year enter the US as unaccompanied minors [2]. Further data show that two-thirds of refugees from Iraq and Myanmar are women and children under the age of 14, and nearly three-quarters of refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, and Syria are women and children under the age of 14[3].

Many refugee children have fled conflict, violence, and war—either with or without their parents, families, or caregivers. More recently, many children have experienced trauma by being separated from their parents upon entering the United States [4]. The experiences these children endure have impacts on their physical, mental, emotional, and behavioral health and wellbeing, as well as on their life course development. Just as it is important that the United States support the resettlement of asylum seekers, including children and youth, it is equally vital that resettlement infrastructure supports and includes mechanisms for meeting the unique needs of this group—specifically, high-quality mental health services and opportunities for mental health promotion, alongside quality physical health care and education.

Stressors and Mental Health Needs

Refugee children and youth, specifically those who have experienced trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), have different developmental needs than their counterparts who are not refugees. ACEs are traumatic events experienced by children that shape their development and can lead to negative outcomes in adolescence and adulthood, including disruptive behavior, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.

These children may experience myriad ACEs in their countries of origin and during their asylum-seeking process, such as political unrest, war, violence, insufficient living conditions, death or loss of family members, chronic fear, and poverty. Upon arriving in the United States, children may experience additional stress by being separated from their parents and by trying to adapt to a new and unfamiliar culture. Additional post-resettlement stressors may include lack of access to resources, financial stress, and insufficient living conditions, as well as language barriers, cultural misunderstandings, family separation, and the struggle to reconcile new cultural beliefs with culture of origin. These stressors—in addition to institutional and societal marginalization, discrimination and harassment from peers and law enforcement, feelings of loneliness, and internalization of stereotypes—can result in negative health outcomes for children and youth.

Refugee Resettlement

Physical and emotional wellness, as well as access to healthcare, are foundations for successful resettlement. Without feeling healthy, it is difficult to work, go to school, or take care of a family.

“Refugee Health,” Office of Refugee Resettlement [5]

Children and youth have unique needs, and consequently, policies and mental health programs should focus on addressing the traumatic and assimilation-related stressors that are distinctive to this population. The US Department of State’s Reception and Placement program works with nine domestic resettlement agencies to place refugees in communities based on each incoming refugee’s need and available resources. Their services include mental health supports and assistance for language, housing, education, medical care, and employment services. Assistance from this program ends three months after arrival, though there are opportunities for states to work with nongovernmental organizations to provide longer-term assistance.

With respect to health care services, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in the US Department of Health and Human Services focuses on health promotion, acknowledging that physical health and emotional wellness (or mental health) are interconnected. Within the first 90 days of arrival, refugees are required by the ORR to undergo a mental health screening, yet screening criteria vary by state. Common diagnoses for refugees include post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

Despite the stressors that refugees face, a number of refugee children and families do not receive mental health services due to concerns over deportation, family separation, stigma, and negative cultural views of mental health services. Further, inadequacies in the US resettlement system and infrastructure—such as inefficiencies in workforce development and cultural competence, and lack of transportation and access to information and resources—can contribute to refugee children and families not accessing services.

Addressing Needs and a Future Course of Action

Currently, government programs do not provide adequate and sustained mental health promotion, screening, and treatment for children and their families upon arrival in the United States. While it may be difficult to address all challenges that refugees face in accessing these services, there are several areas where small changes and increased awareness can yield great results.

Improve strategies to engage children and youth. Methods for increasing engagement of children, youth, and families in mental health services may include social support, community outreach, and health education. These increased opportunities for engagement may mitigate social isolation and further promote discussion about underlying exposures to trauma.

Address mental health concerns in school settings. Schools are often one of the first places refugee children and youth begin socializing and developing relationships with US-born peers and adults. Schools are also where they take initial steps in navigating a new culture. School-based mental health programs can provide an outlet for children and youth to address ACEs and overcome barriers they may encounter during and after resettlement. It is critical that teachers, school counselors, psychologists, and administrators be trained to support this subgroup of students in their academic, physical, and mental well-being.

Engage primary care physicians in providing mental health care. Primary care physicians play an important role in refugee mental health care. Access to mental health services generally begins with their primary care physician; thus, this segment of the workforce needs to be culturally competent when providing mental health care or resources. Consideration should be given to the patient’s potential fear regarding legal status, distrust of authority, and perceived power dynamics between patient and physician. Further, it is vital that physicians be aware of their own biases and limitations when working with refugee children, youth, and families.

Acknowledge cultural influences in mental health services. Families may not seek help for their child due to the stigma surrounding mental illness, and in turn, a child may not reveal their struggles to their parents. A number of approaches can be taken to combat cultural stigma, including:

- Provision of culturally appropriate prevention opportunities, screening, and treatment through school-based programs, where refugee children and youth are more likely to access services;

- Support for the development of a community support system through which community leaders serve as liaison between the refugee population and mental health professionals; and

- Development of a culture of metal health promotion for refugee children and youth through public-private partnerships at the national, state, and local levels.

The level of trauma that refugees experience has a recognized affect on their mental health and well-being, but we have the opportunity to help them rebuild and change the trajectory of their futures. The United States has long benefited from the energy, creativity, and hard work of immigrant populations; it is therefore essential that we care for the full range of healthcare needs of refugee children and youth.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Children of asylum-seekers have likely endured many traumatic events by the time they arrive in the US. Our newest #NAMPerspectives argues that existing mental health supports are inadequate to serve these children and should be strengthened: https://doi.org/10.31478/201808a #investinkids

Tweet this! Children of asylum-seekers have likely endured many traumatic events by the time they arrive in the US. Our newest #NAMPerspectives argues that existing mental health supports are inadequate to serve these children and should be strengthened: https://doi.org/10.31478/201808a #investinkids

![]() Tweet this! “Just as it is important that the United States support the resettlement of asylum seekers, including children and youth, it is equally vital that resettlement infrastructure include high-quality metal health services.” https://doi.org/10.31478/201808a #NAMPerspectives

Tweet this! “Just as it is important that the United States support the resettlement of asylum seekers, including children and youth, it is equally vital that resettlement infrastructure include high-quality metal health services.” https://doi.org/10.31478/201808a #NAMPerspectives

![]() Tweet this! The United States has provided asylum to more than 3 million refugees since 1975. In addition to providing physical safety, we should also be caring for the mental health of these refugee families: https://doi.org/10.31478/201808a #NAMPerspectives

Tweet this! The United States has provided asylum to more than 3 million refugees since 1975. In addition to providing physical safety, we should also be caring for the mental health of these refugee families: https://doi.org/10.31478/201808a #NAMPerspectives

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- US Department of State. n.d. Refugee admissions. Available at: https://www.state.gov/j/prm/ra/ (accessed June 28, 2018).

- Bridging Refuge Youth & Children’s Services. 2018. Refugee 101. Available at: http://www.brycs.org/aboutRefugees/refugee101.cfm (accessed June 28, 2018).

- US Department of State. 2017. Fact sheet: Fiscal year 2016 refugee admissions. Available at: https://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/factsheets/2017/266365.htm (accessed June 28, 2018).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Statement on harmful consequences of separating families at the US border. Available at: http://www8.nationalacademies.org/onpinews/newsitem.aspx?RecordID=06202018 (accessed June 28, 2018).

- Office of Refugee Resettlement. n.d. Refugee health. Available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/refugee-health (accessed June 28, 2018).