Nursing, Trauma, and Reflective Writing

The young nurse returned to room seven. Finishing up her charting just a moment earlier, she glanced at her watch and knew she couldn’t postpone going into his room any longer, despite the disconcerting vibe she got each time she went in there.

Room seven was still dark and the patient was still grinning. Glasses were still cloudy and eyes were still staring. Scanning the room, the young nurse realized that she and the doctor had left the place in shambles in their rush to escape. As she started to gather the waste, she noted a capped, pink syringe, the 20-gauger from the failed attempt [at IV insertion] earlier. The young nurse inwardly groaned. Had her manager made it in there before her, she would have never heard the end of it: You left a needle within reach of an encephalopathic patient?? What were you thinking?!

Well, she certainly was thinking now. She picked up the needle and felt a stab.

Jordana Kozupsky refers to herself in the third person in this excerpt from a narrative essay, “My Infected Reality,” that she composed in a writing course for graduate nursing students in 2015. Here, the nurse returns to the room of a patient infected with HIV who had violently resisted her and a physician’s earlier attempts at inserting an IV.

Did the needle pierce the patient’s skin before penetrating her own, thus exposing her to a serious infectious disease? She can’t be sure, and Jordana’s reality becomes infected by panic, flashbacks, and nightmares, leaving her unable to take the step of getting tested. Her writing explores an unfortunately common workplace trauma for nurses—needlestick and its aftermath—by echoing its disturbing effects on her life.

In 2010 at the Hunter–Bellevue School of Nursing (HBSON) in New York, Diana Mason, PhD, RN, FAAN; Joy Jacobson, MFA; and Jim Stubenrauch, MFA, devised a curriculum designed to address the academic challenges displayed in the writing of many nursing students: plagiarism, poorly organized ideas, and inadequately sourced scholarly material [1]. Though there are various theories about how best to approach such deficits, what distinguished this course was that it sought to improve scholarly performance by encouraging reflection and engagement in writing as a process of discovery and artistic exploration. And because it has been shown that when health care workers read literary works and write reflective narratives, it enhances their interpersonal skills, increases job satisfaction and retention, and promotes empathy [2,3], the nursing curriculum was crafted with a dual focus: to build students’ resilience and improve their academic writing. The course was called Writing, Communication, and Healing.

The need for innovative approaches to burnout prevention in the health professions is immense. In one survey of ICU nurses, 85 percent said they wanted a better job, 64 percent reported insomnia, and almost half told of being “emotionally exhausted”—all risk factors for depression [4]. A February 2017 report from the Johnson Foundation’s Wingspread Center concluded that as many as half of new nurses leave the profession in their first two years of work and that all nurses are susceptible to burnout at any stage of their careers [5]. Among other recommendations, the report advises individual nurses to create a “resiliency plan” and institutions to reframe burnout as a workplace injury.

The HBSON writing course model presumes that all people are innate storytellers, even those who have little confidence as writers. This instinct can be useful in fostering resilience, usually defined as a person’s ability to recover quickly from trauma and to restore optimism in the face of adversity [6]. Although resilience in health care providers may be recognized as a necessary quality, it is rare for health care systems or medical and nursing schools to make room for the genuine reflection it requires.

In the HBSON writing course, which is still being taught, nursing students begin to tell their own stories, to experiment with voice and point of view, and to hear their own work and each others. Such writing is not always easy for nurses, but when given support and instruction, many draft resonant narratives about patients whose lives they’ve saved and those who’ve died; about workplace violence and bullying and medical error; about their personal experiences of love and divorce, pregnancy and miscarriage, immigration, intimate partner violence, illness, and death—in short, about their losses, struggles, and triumphs. (One exceptional student’s progress with this model has recently been documented [1].) Also, engagement, investment, and pride in one’s own writing are often crucial first steps in the development of writing competence [8].

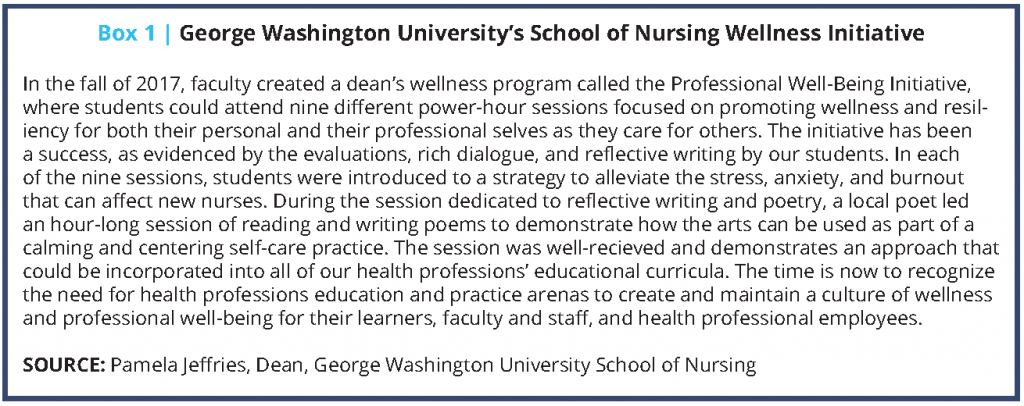

Many health professions schools are now focusing initiatives on promoting a culture of wellness. George Washington University’s School of Nursing is one such example (see Box 1).

What allows any of us to acknowledge and respond to our own suffering and that of others? A writing community can guide clinicians in igniting a spark of originality—one that permits them to respond more fully to themselves, to one another, and to their patients.

Writing as Reflection, Community as Strength

Several pedagogical models have informed this writing curriculum.

Writing instructor and journalist Donald Murray wrote that teaching writing as a process of discovery requires instructors to recognize that their first task is to listen to students’ works in progress—“We are not the initiator or the motivator; we are the reader, the recipient”—challenging the received notion that it’s the instructor’s job to edit and correct student papers [8]. One-to-one conferences and guided peer-to-peer feedback strengthen students’ ability to revise their own work and to consider writing a process rather than an event.

Physician Rita Charon and fiction writer Nellie Hermann from Columbia University’s Narrative Medicine program view clinicians’ “narrative capacity”—an essential aspect of their ability to hear and attend to patients’ stories—as a quality strengthened by reflective writing: “Writing is how one reflects on one’s experience so that it can be apprehended and then comprehended” [9].

James Pennebaker and colleagues have studied the effects of expressive writing—writing for 20 minutes a day for several days about a single difficult or traumatic experience—on various populations’ ability to cope with stress and trauma. One literature review found many studies supporting positive effects of expressive writing, perhaps because it imposes structure on the chaos of emotional upheaval, demanding “a different representation of the events in the brain, in memory, and in the ways people think” [10]. Expressive writing has even been shown to speed wound healing [11].

Similarly, poet Gregory Orr examines the ways in which the reading and writing of lyric poetry “orders and dramatizes our subjectivity and externalizes it as language” [12].

Louise DeSalvo integrated Pennebaker’s method into an immersion program in writing as a method of healing from trauma, emphasizing that not all writing culminates in what she calls a “healing narrative.” Such writing, she says, possesses five characteristics [13]:

- It portrays experience concretely, in rich detail.

- It connects feelings to events.

- It balances positive and negative emotion, even as it describes difficulties.

- It provides insight and reflection.

- It relates a full and comprehensible story.

“Going public” is the last crucial step in DeSalvo’s model. She goes so far as to call the sharing of personal written stories “the most important emotional, psychological, artistic, and political project of our time” [13]. In the HBSON course, in a culmination of the community fostered during the semester, nursing students read from their essays to one another in the last class.

Although this curriculum was created as an academic course, it has been adapted for use in clinical arenas as well. A writing program for working clinicians may include any or all of the following:

- Meetings begin with “quick-writes,” in which participants write without pausing for 3 to 20 minutes in response to a prompt such as a poem.

- Writers have the option of reading their quick-writes and more formal writings aloud, without comment from others.

- Participants agree to write daily, in concrete ways, about their lives and work. Daily journaling is a terrific tool for strengthening reflective capacity and overall writing skill.

- Group members write about scientific studies in online discussion groups, telling their own stories as they analyze research methods and findings. Studies showing the consequences of professional burnout have generated lively responses from nurses.

- Participants establish writing goals, especially for longer works, including at least two drafts and significant revision.

Support in the form of a regularly scheduled writing group, with set goals, can enhance nurses’ confidence as writers and help them maintain momentum [14,15].

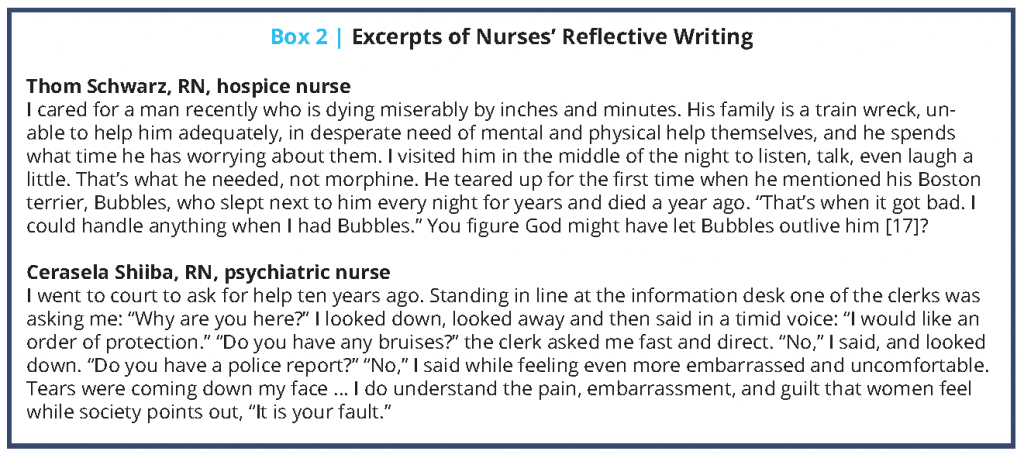

It can be very hard for busy clinicians to maintain a writing practice, but the benefits are clear. In a follow-up survey of HBSON graduate and undergraduate nursing students who took the writing course (23 anonymous responses to 114 e-mailed surveys), nearly all said that the course positively affected their ability to be empathetic with patients and families and that they better understood academic and professional writing to include revision. Perhaps most significant was that 64 percent continued to use reflective journaling at least once per week “to help me deal with the stresses of my job,” 17 percent of them daily (see Box 2).

Jordana Kozupsky is an outstanding exemplar. She has completed her coursework for her doctorate of nursing practice and now heads a peer-tutoring program in writing at her school of nursing. She has also published a piece of writing that began as an assignment in the writing class. In “Teamwork: Caring for Ourselves and Each Other,” Kozupsky reconceives the clinical work place as a community of sustenance rather than a zone of depletion.

She writes, “We all become nurses for the same reason: to help people out. And in this field, ‘people’ doesn’t only denote patients; it denotes our fellow nurses as well” [16].

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Burnout in clinicians is widespread, and innovative approaches to combating burnout are needed. Reflective writing provides clinicians with a way of understanding their own trauma in a way they may not have considered before: http://ow.ly/GxDT30ky5A5

Tweet this! Burnout in clinicians is widespread, and innovative approaches to combating burnout are needed. Reflective writing provides clinicians with a way of understanding their own trauma in a way they may not have considered before: http://ow.ly/GxDT30ky5A5

![]() Tweet this! Reflective writing is not only for poets. Just 20 minutes a day can help clinicians process the trauma they see when caring for patients and assist in building resilience: http://ow.ly/GxDT30ky5A5

Tweet this! Reflective writing is not only for poets. Just 20 minutes a day can help clinicians process the trauma they see when caring for patients and assist in building resilience: http://ow.ly/GxDT30ky5A5

![]() Tweet this! Reflective writing can build confidence, support resilience, reduce burnout and create a community among clinicians. Read about successful programs in our latest NAM Perspectives paper: http://ow.ly/GxDT30ky5A5

Tweet this! Reflective writing can build confidence, support resilience, reduce burnout and create a community among clinicians. Read about successful programs in our latest NAM Perspectives paper: http://ow.ly/GxDT30ky5A5

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Jacobson, J. 2016. “Like a page waiting for music”: Nursing, poetry, and autonomy. In Keeping reflection fresh: A practical guide for clinical educators, edited by A. Peterkin and P. Brett-MacLean. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press.

- Clary, B. 2008. Program evaluation, literature and medicine program, final report. Available at: http://www.okhumanities.org/Websites/ohc/images/Programs/Literature_and_Medicine/Lit___Med_Program_Evaluation.pdf (accessed June 6, 2018).

- DasGupta S., and R. Charon. 2004. Personal illness narratives: Using reflective writing to teach empathy. Academic Medicine 79:351-356. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013

- Sexton, J. D., J. W. Pennebaker, C. G. Holzmueller, A. W. Wu, S. M. Berenholtz, S. M. Swoboda, P. J. Pronovost, and J. B. Sexton. 2009. Care for the caregiver: Benefits of expressive writing for nurses in the United States. Progress in Palliative Care 17(6):307-312. https://doi.org/10.1179/096992609X12455871937620

- Johnson Foundation Wingspread Center. 2017. A gold bond to restore joy to nursing: A collaborative exchange of ideas to address burnout. Available at: https://ajnoffthecharts.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NursesReport_Burnout_Final.pdf (accessed June 6, 2018).

- Turner, S. B. 2014. The resilient nurse: An emerging concept. Nurse Leader 12(6):71-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MNL.2014.03.013

- Bean, J. C. 2011. Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Murray, D. 2009. Teach writing as a process not product. In The essential Don Murray: Lessons from America’s greatest writing teacher, edited by T. Newkirk and L. Miller. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

- Charon, R., and N. Hermann. 2012. A sense of story, or why teach reflective writing? Academic Medicine 87(1):5-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823a59c7

- Pennebaker, J. W., and C. K. Chung. 2011. Expressive writing: Connections to physical and mental health. In The Oxford handbook of health psychology, edited by H. Friedman. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Koschwanez, H. E., N. Kerse, M. Darragh, P. Jarrett, R. J. Booth, and E. Broadbent. 2013. Expressive writing and wound healing in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine 75(6):581-590. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829b7b2e

- Orr, G. 2002. Poetry as survival. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- DeSalvo, L. 2000. Writing as a way of healing. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Shellenbarger T. 2017. In the company of writers. Nurse Author & Editor 27(1). Available at: http:// http://naepub.com/collaboration/2017-27-3-3 (accessed June 6, 2018).

- Stone, T., T. Levett-Jones, M. Harris, and P. M. Sinclair. 2010. The genesis of “the Neophytes”: A writing support group for clinical nurses. Nurse Education Today 30(7):657-661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.12.020

- Kozupsky, J. 2016. Teamwork: Caring for ourselves and each other (blog post). American Nurse. Available at: http://www.theamericannurse.org/2016/04/07/teamwork-caring-for-ourselves-and-our-patients (accessed June 6, 2018).

- Schwarz, T. 2016. Hospice nurse Thom Schwarz on God, angels, and speaking the unspeakable (blog post). HealthCetera. Available at: http://healthmediapolicy.com/2016/09/15/hospice-nurse-thom-schwarz-on-god-angels-and-speaking-the-unspeakable (accessed June 6, 2018).