The Case for Health Literacy - Moving from Equality to Liberation

The majority of health literacy research focuses on providing support to patients and strengthening individual health literacy skills. The work is much needed and important but places the onus or responsibility to increase health literacy solely on those who are mistreated by a complex system of policies, procedures, and institutions. Instead, as in other market-driven industries, the responsibility should fall on the companies and organizations that sell health care to maintain their margins and profits. Very few other industries could survive by providing poor communication and hard-to-understand information to their clients and consumers.

Health Literacy: From Equality to Liberation

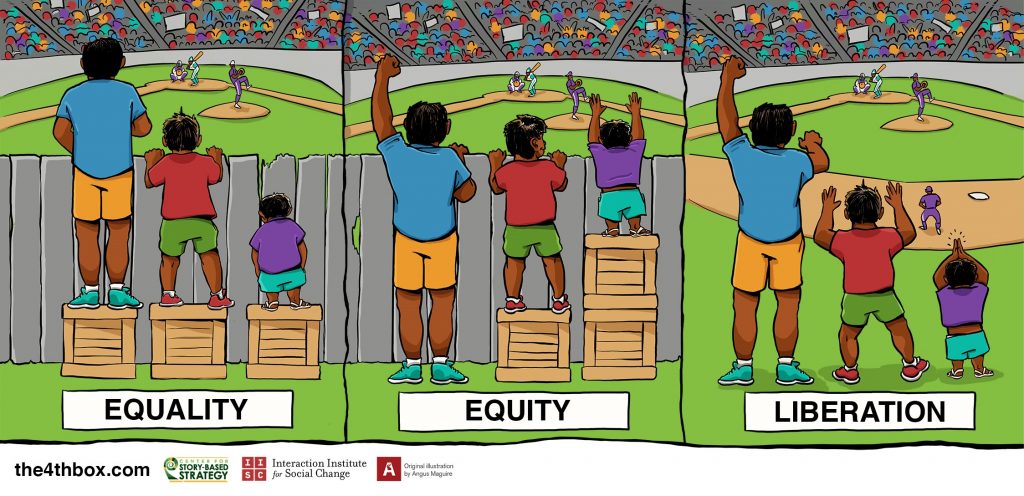

In Figure 1, we have modified the image to describe how to move from equality to equity and then liberation. The Equality image represents the traditional approach in health care, which turns a blind eye to health literacy and fails to address the differential impact on individuals and populations. The Equity portion of the image represents more equitable care by providing patient and caregiver supports, such as health literacy. Health literacy is a life skill that should be taught in school with reading, writing, and math. For now, it is imperative that we teach health care providers and staff to provide health literate care. It is good business to meet your customers where they are and make their experience as easy and pleasurable as possible. This is at the heart of good customer service.

The health care system must strive to achieve the liberation represented in the third image. With liberation, complex systems and information are broken down to remove the fence blocking patients from getting what they need and truly meet patients where they are. Liberation also involves teaching health care providers to actively listen and build care that is centered around the person’s needs. We need to liberate patients, caregivers, and family members from complex information demands and confounding systems. The responsibility of the health system is to establish health literate organizations and care. That responsibility will become heightened as payment realigns from volume to value and truly incentivizes health deliverers to provide high-quality care. Ineffective communication and inefficient systems of care delivery that do not emphasize listening to and learning about a patient’s life circumstances will become a much rarer sight as the health care industry transforms its business models to thrive under these new reimbursement mechanisms.

Moreover, the case for health literacy grows stronger every day. Those organizations and entities that embrace and adopt health literate principles early will gain a strategic advantage over the competition. Health literacy is still a relatively young field from a research perspective. However, based on the limited studies we have, plenty of preliminary evidence shows that adopting health literacy universal precautions can improve the quality of care and enhance the care experience, while reducing health costs (both for individuals and the system) and strengthening our efforts to achieve health equity [1].

Returning to the image, there are numerous planks that need to be removed from the fence to liberate patients fully from confusion and frustration, allowing them to make informed decisions about what care to receive, how to receive it, and where and when to receive it. We need to value the knowledge of all involved: the patients as experts in their lives and the providers of care as experts in the field. We will highlight some of these planks/barriers in the remainder of this discussion paper, keeping in mind that this is just a start. Many other barriers need to be addressed before patients, caregivers, and family members will be unshackled from health literacy challenges. The responsibility of those working within the health system is to identify and remove all of these challenges. This is one way we can meet the quadruple aims to provide higher-quality care at a lower cost, while increasing the care experience for both patients and health professionals [2].

Figure 1 | Equality, Equity, and Liberation

Source: Image by Angus Maguire, Interaction Institute for Social Change, adapted from Craig Froehle.

Siloed Delivery

One systematic change starting to be addressed is the siloed delivery of health care. Many Americans go to outpatient doctors that are outside of the hospital systems to which they are admitted. Others get prescriptions filled at drug and grocery stores that are not connected to any health system. This lack of care coordination across siloes can be a huge barrier to quality care and can lead to further patient confusion. As we move toward more team-based care delivery, we also need to adopt medical home models or move to accountable care organizations that coordinate care across inpatient, outpatient, home care, therapy, and other settings. We cannot leave patients who have little training and understanding of how the health system works on their own to navigate and manage their care across disjointed delivery systems.

Volume-Based Reimbursement

With the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ramping up the transition from volume- to value-based reimbursement, a recent survey found that over half of health executives (55 percent) expect value-based purchasing to be the norm by 2020 [3,4,5]. This move will go a long way to freeing up health professionals’ time to communicate with patients in more meaningful ways. Current volume-based reimbursement actually discourages health systems from providing good communication, because if providers do not do a good job and a patient comes back, they make more money. We have already seen a change with the implementation of reimbursement penalties around readmissions. Since hospitals may not get reimbursed if they fail to adequately provide support to patients, new measures call for hospitals to make discharge information easier for patients to understand. New practices also require hospitals to provide clinical, social, and community supports to patients after they have left the hospital, to ensure they are not readmitted due to further complications.

Lack of Transparency

A remaining and systemic barrier in the health care system is the lack of transparency in terms of cost and quality of care. When a car needs repairs, a mechanic usually provides a detailed estimate of the costs for the parts and labor. In fact, a customer will often want to know the estimated costs for the repairs and, in some cases, attempt to negotiate a lower price. Even before going to see a mechanic, a consumer can use various resources to determine which mechanics provide high-quality services for a fair price. If the customer cannot or is unwilling to pay the repair costs, the customer can and will take their car to a different mechanic. In short, the customer possesses the power to choose and negotiate. If a vehicle’s constant-velocity joint, for example, needs to be replaced, the customer will more than likely ask what it is and what it does. However, the health care industry lacks the same level of transparency, as a patient rarely receives an estimate of the costs for a procedure and there is no room for the patient to negotiate a lower price.

Medical terms are often listed on an insurance explanation of benefits or clinical notes without definitions. Patients, family members, and caregivers are more likely to understand “the part of the jaw bone that acts like a hinge” compared to the medical term “temporomandibular joint.” Reaching equity, and ultimately liberation requires complete transparency across the health care industry.

Electronic Health Record (EHR) Interoperability

Banks depend on technology systems to make electronic deposits and withdrawals for customers each day. The electronic transfer of money from one bank account to another, either within a bank or across different banks, takes place automatically. If a bank’s technology system cannot communicate with other banks’, it is very likely that bank may go out of business. In this context of interoperability, different software and computer systems communicate, exchange, and use information without any restrictions. Health care systems and providers who accept Medicare payments are required to install electronic health record systems and provide evidence that the EHR system is in use. EHR systems are meant to promote health information exchange and improve patient outcomes [6]. However, numerous private companies have developed different EHR hardware and software systems that are not interoperable, and they fear that doing so would expose proprietary information that might make them lose their share of the market. As a result, instead of liberating patients by breaking down information exchange barriers, the lack of EHR interoperability increases the demands placed on patients. Consequently, patients must ensure that information exchange takes place and that all the places they receive care from have their complete health record.

Summary

Proposing health literacy as a key component to transition the health care industry from equality to liberation may appear radical at first. However, as we point out, the changing structure of reimbursement requires that the health care industry implement a liberation business model focused on meeting patients and family members where they are as they describe their needs. We realize that changing business models is disruptive and may introduce market instability. Yet a period of disruption may signal a period of future innovation. Given the current research, we are confident that health literacy is essential to tearing down planks such as siloed delivery, volume-based reimbursement, lack of transparency, and interoperability challenges. Health care organizations and providers who are early health literate adopters will possess a significant market advantage, lower costs, increase satisfaction, improve the care experience for patients and providers, and ultimately improve the population health of the nation. Let us move forward to liberation as equal partners.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Supporting health literacy for all will improve quality of health and medical care, enhance the care experience, and may even lead to reducing health costs. Read a new NAM Perspectives commentary by @rv_rikard and @socialjusticesh: http://ow.ly/3nED30k4cqv

Tweet this! Supporting health literacy for all will improve quality of health and medical care, enhance the care experience, and may even lead to reducing health costs. Read a new NAM Perspectives commentary by @rv_rikard and @socialjusticesh: http://ow.ly/3nED30k4cqv

![]() Tweet this! “We need to value the knowledge of all involved: the patients as experts in their lives and the providers of care as experts in the field.” Promoting health literacy will improve the health care experience for all involved: http://ow.ly/3nED30k4cqv

Tweet this! “We need to value the knowledge of all involved: the patients as experts in their lives and the providers of care as experts in the field.” Promoting health literacy will improve the health care experience for all involved: http://ow.ly/3nED30k4cqv

![]() Tweet this! In our newest NAM Perspectives commentary, @rv_rikard and @socialjusticesh advocate for teaching health care providers to actively listen and build care that is centered around the needs of the patient rather than the provider: http://ow.ly/3nED30k4cqv

Tweet this! In our newest NAM Perspectives commentary, @rv_rikard and @socialjusticesh advocate for teaching health care providers to actively listen and build care that is centered around the needs of the patient rather than the provider: http://ow.ly/3nED30k4cqv

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Hudson, S., R. V. Rikard, I. Staiculescu, and K. Edison. 2017. Improving health and the bottom line: The case for health literacy. In Building the case for health literacy: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Appendix C.

- Bodenheimer, T. and C. Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine 12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2018. National impact assessment of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) quality measures reports. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/National-Impact-Assessment-of-the-Centers-for-Medicare-and-Medicaid-Services-CMS-Quality-Measures-Reports.html (accessed April 18, 2018).

- Brown, B. 2015. Value-based purchasing: Why your timeline just got shorter. Health Catalyst. Available at: https://www.healthcatalyst.com/value-based-purchasing-why-timeline-just-got-shorter (accessed April 18, 2018)

- Lazard. 2017. Global healthcare leaders study 2017: Executive summary. New York. Available at: https://www.lazard.com/media/450169/executive-summary-lazard-healthcare-leaders-study-2017.pdf (accessed April 18, 2018)

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-148.