Health Literacy as an Essential Component to Achieving Excellent Patient Outcomes

Introduction

The demographic makeup of the United States is rapidly changing, and these trends will continue to reshape the nation in the coming decades. The aging and evolving racial and ethnic composition of the U.S. population has placed the nation in the midst of a profound demographic shift, and health care organizations must address and adapt to this change. The U.S. population is more diverse than ever before in terms of race, ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and education level. Trends of increased fertility, decreased mortality, and increased immigration have contributed to the growth of the U.S. population (Shrestha and Heisler, 2011). Minority groups are the fastest-growing demographic, currently accounting for one-third of the U.S. population (Betancourt et al., 2012). In order to adequately serve these changing demographics, we believe that health care organizations must refocus their efforts to provide all persons with the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions. Such refocusing requires that senior organizational leadership enhances its efforts to promote, sustain, and advance an environment that supports principles of health literacy. In our opinion, establishing an Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy is essential to operationalize health literacy across an organization and enhance its viability, focus, and sustainability.

Background

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (ACA, 2010). More recently, we have come to understand that health literacy is defined by the interaction between an individual’s skills and abilities and the demands of the health care system. Ninety million American adults are unable to understand or act on health information they receive, and only 12 percent of English-speaking adults have proficient health literacy skills (HHS, 2010; White and Dillow, 2003). Research indicates that persons with low health literacy have less knowledge about disease management, less use of preventive services, and higher hospitalization rates (Baker et al., 2002); incur higher health care costs (Howard et al., 2005); have an increased risk of mortality (Baker et al., 2007); and report poorer health status than persons with adequate literacy skills (IOM, 2004).

We believe that heightened awareness and recognition of health literacy as an essential component in the nation’s focus on patient-centered care has led to broad recognition that health literacy is a national priority. Such recognition is reflected in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), in which health literacy is specifically mentioned. Somers and Mahadevan (2010) state that individuals with low health literacy skills are the least equipped to benefit from the ACA. The World Health Organization (2013) has identified health literacy as an asset for both individuals and communities. The federal government has also recognized the importance of health literacy, considering it vital to patient-provider communication and health care quality (HHS, 2010). Additionally, accreditation bodies, such as the Joint Commission (2010), have stressed the importance of health literacy to patient safety and encouraged its integration into practice.

In response, we have seen that health care organizations are implementing initiatives in an effort to decrease the complexity of demands being placed on individuals accessing care. In addition, with the passing of ACA, there is a vital need to prepare individuals that are accessing a very complex health care system for the very first time.

Health Literacy as an Essential Component in a Health Care Organization

In an effort for organizations to be prepared to meet the needs of changing demographics, a baseline assessment of organizational readiness should be conducted to ensure effective communication, cultural competence, and patient-centered care. Such an assessment will help to identify areas of best practice as well as areas in need of improvement. Metrics can be established to assist in monitoring progress and sustainability. Such data can help to develop or modify services, programs, and initiatives needed to appropriately meet the needs of populations served. Enhancing health literacy efforts requires changes in professional and organizational practices to augment the alignment of health care needs with the abilities and skills of the communities served.

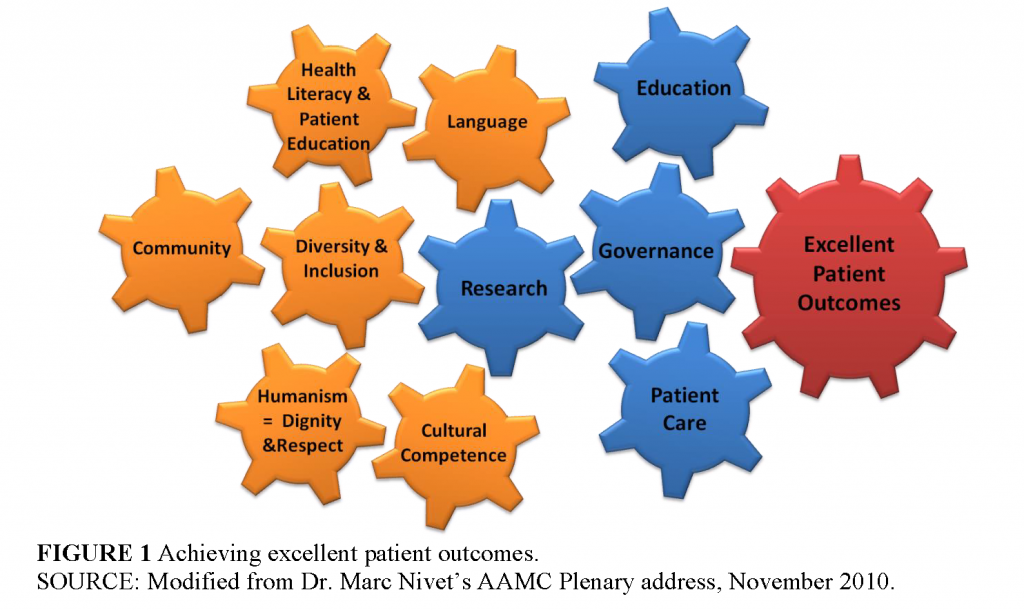

In order to deliver excellent patient outcomes, we believe that organizations should identify health literacy as an essential core component of their mission, as shown in Figure 1. A multiyear strategic plan should be established to create domains, goals, and action steps that foster a culture of diversity, inclusion, and health literacy across the organization. The IOM discussion paper Attributes of a Health Literate Organization (Brach et al., 2012) can assist in providing the foundational framework.

Integrating Health Literacy into the Organization

The launching of an Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy is, in our opinion, critical to enhancing health literacy’s visibility and importance to an organization’s mission and vision. This approach assists with the selection of individuals whose scope of work and responsibility is centered on health literacy. It provides visibility and assists with setting organizational expectations and accountability.

An Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy is able to incorporate health literacy across all areas and vehicles throughout the organization. It can collaborate with human resources and onboarding of new employees in an effort to educate them about the culture of the organization and set expectations about effective communication, cultural awareness, and language. Collaborating and driving processes for marketing and public relations is another area of opportunity and integration with an office approach. Opportunities for the development of guidelines and policies for internal and external print material, as well as processes for those participating in the development of patient education materials, can be developed across the entire organization. Health literacy representation on organizational committees ensures that health literacy is being addressed from the initial planning through the implementation and evaluation of all initiatives.

When launching an Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Health Literacy, we believe that health literacy expectations can be consistently communicated and incorporated into all practices. Senior leadership can assist with the expectation of a culture in which all employees and practitioners utilize a “universal precaution approach” and do not make assumptions about the health literacy level of any consumers of health care. The “universal precaution approach” will make it easier for all persons to access, navigate, understand, and use information and services to take care of their health and make informed decisions. This approach should incorporate the following tenets:

- Always ask about an individual’s preferred language to discuss health care.

- Perform a learning needs assessment that assists in individualizing communication for each individual’s needs, which includes

- educational level,

- readiness to learn,

- learning preferences, and

- cultural, developmental, and religious considerations.

- Communicate and educate using plain language.

- Incorporate “teach-back” and document outcomes.

- Always ask “what questions do you have?” rather than “do you have any questions?” to provide a comfortable, shame-free environment.

Health Literacy Sustainability

To promote sustainability, organizations can develop system-wide Patient Education and Health Literacy Committees that promote, sustain, and advance an environment that supports principles of equity, diversity, and health literacy. To raise awareness of health literacy in the workforce, the authors believe that organizations should establish various interdisciplinary system-wide intramural education initiatives that can help to transform the organization’s climate and promote the delivery of excellent, safe, patient-centered care.

Ongoing education and the provision of resources are essential to sustainability. Health care professionals need to understand the consequences associated with low health literacy and the impact it has on health outcomes. As health care environments and populations change, ongoing education will help reinforce professionals’ responsibility to provide health information to their patients in a way in which they can understand.

Summary

Efforts to develop health literacy skills can increase knowledge, improve employee-to-employee communication, enable us to better serve our increasingly diverse patient population, and empower our communities to be active partners in their care. As organizations establish strategies to help improve the health of the nation overall, success will depend on their efforts in building trusted partnerships with communities and collaborate with community members to take an active role in their health and well-being.

To strive for excellent patient outcomes, the diverse needs of patients must be met. All health care professionals need a foundational level of health literacy knowledge and an understanding of the diverse populations for whom they are providing care. Health literacy is, we believe, an essential component in organizational efforts to reduce health care disparities. Launching an Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy will help establish a systematic, integrated, and sustainable approach in all areas of a health care organization.

References

- Baker, D. W., J. A. Gazmararian, and M. V. Williams. 2002. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Public Health 92(2):1278-1283. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278

- Baker, D. W., M. S. Wolf, J. Feinglass, J. A. Thompson, J. A. Gazmararian, and J. Huang. 2007. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Archives of Internal Medicine 167(14):1503-1509. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503

- Betancourt, J. R., M. R. Renfrew, A. R. Green, L. Lopez, and M. Wasserman. 2012. Improving patient safety systems for patients with limited English proficiency: a guide for hospitals. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; AHRQ Publication No. 12-0041. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/lepguide.pdf (accessed May 26, 2020).

- Brach, C., D. Keller, L. M. Hernandez, C. Baur, R. Parker, B. Dreyer, P. Schyve, A. J. Lemerise, D. Schillinger. 2012. Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201206a

- HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion). 2010. National action plan to improve health literacy. Available at: http://www.health.gov/communication/hlactionplan

(accessed December 12, 2013). - Howard, D. H., J. A. Gazmararian, and R. M. Parker. 2005. The impact of low health literacy on the medical cost of Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Medicine 118(4):371-377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.010

- Institute of Medicine. 2004. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10883.

- Joint Commission. 2010. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient and family-centered care: A roadmap for hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Publications/AdvancingEffectiveCommunicationCulturalCompetencePFCC.aspx (accessed May 26, 2020).

- Shrestha, L., and E. Heisler. 2011. The changing demographic profile of the United States. Available at: http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32701.pdf (accessed December 12, 2013).

- Somers, S.A., and R. Mahadevan. Health literacy implications of the Affordable Care Act. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., November 2010. Available at: https://www.chcs.org/resource/health-literacy-implications-of-the-affordable-care-act/ (accessed May 26, 2020).

- White, S., and S. Dillow. 2005. Key concepts and features of the 2003 National Assessment of adult literacy (NCES 2006-471). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED489067.pdf (accessed May 26, 2020).

- WHO (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe). 2013. Health literacy: The solid facts. Copenhagen, Denmark. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/190655/e96854.pdf (accessed

December 12, 2013).