Case Study: Nationwide Children's Hospital: An Accountable Care Organization Going Upstream to Address Population Health

As managed care organizations (MCOs) and accountable care organizations (ACOs) begin to invest in population health improvement, they are faced with significant and diverse challenges. This is especially true in pediatric care; without the leverage of a national payment system and standard-setting authority like Medicare, those providing and paying for pediatric care must navigate complex political, cultural, and financial environments that are unique to each state and local community. Though many MCOs and ACOs already engage in population health and prevention work, not all invest in upstream interventions that address the root social determinants of health. These social determinants of health contribute to long-term wellness—or sickness—and play a large role in chronic disease development. A key question remains: what are the factors that influence leadership in MCOs and ACOs to move upstream and invest in the social determinants of health?

In an effort to aid MCOs and ACOs in the early stages of population health strategy development, the Nemours Foundation has set out to spotlight outstanding systems that provide examples of success and demonstrate the flexibility that may be available under existing Medicaid managed care authorities. One such system is Nationwide Children’s Hospital (NCH); by further understanding NCH’s experience in upstream investment, we hope to illuminate pathways for other MCOs and ACOs to focus on social determinants in their population health strategy.

NCH is a large academic medical center in Columbus, Ohio, with more than 1 million patient visits per year and 25,000 inpatient admissions. NCH also co-owns a pediatric ACO called Partners for Kids (PFK) and carries full financial risk for about 330,000 children in the Medicaid program. While not focused on obesity prevention, PFK implements an upstream population health strategy using predominantly Medicaid funding that may be widely applicable to many disease prevention efforts including childhood obesity.

This paper provides a brief history of NCH and the context in which its population health strategy was developed, an analysis of the accelerators of and barriers to success, and concludes with a review of lessons learned.

History and Context

NCH embarked on its risk-bearing journey in the 1990s following the health maintenance organization (HMO) era. With considerable experience in risk contracting, and as a result of rampant HMO failures, NCH decided to launch its own risk-bearing entity—PFK—in 1994. Rather than risk additional HMO failures, which had historically left the system with unpaid bills of up to $2 million, NCH launched PFK to take some measure of control, address cost challenges, and improve care quality for approximately 13,000 children.

In 1997, PFK signed its first contract. At the time, PFK was not called an ACO as the term did not exist. Moreover, cost-saving panel management strategies were initially viewed by some hospital executives as part of a contracting strategy to attract payers and outperform traditional Medicaid by accepting risk for children in their region of the state. This approach also limited NCH’s susceptibility to external, financially destabilizing forces. Once the cost-benefit was demonstrated in PFK’s first contract, more MCOs entered into contracts. With this more stable financial position, NCH and PFK continued on a gradual progression toward risk-bearing and population health.

In 2008, PFK was designated as an intermediary insurance organization (and unofficially as an ACO) by the state of Ohio. This designation is allowable under state discretionary flexibility, and allowed NCH and PFK to carry risk and provide and pay for care. PFK maintained contracts with MCOs that provide largely an administrative or claims role. Eventually, the state of Ohio transitioned all Medicaid beneficiaries, with a few exceptions, into managed care.

As PFK took on more risk by serving more Medicaid children who were now enrolled in managed care, it became apparent that to further improve outcomes and save money in the long run, NCH needed to invest in upstream population health activities that addressed social determinants of health. This signaled a shift from population management for their patient panels to population health for a geographically defined population. NCH, through PFK, began working to address the upstream, nonclinical needs of the geographic population to improve downstream clinical outcomes.

Under the leadership of Steven Allen, chief executive officer (CEO) of NCH, and Tim Robinson, chief financial officer (CFO) of NCH and board member and treasurer for PFK, NCH now manages a large portfolio of population health initiatives that is fully integrated into the operation of the health system. Examples of such initiatives are included in Appendix A.

Accelerators and Barriers

Developing a population health strategy was a multipronged and multi-stage approach at NCH. Though NCH’s current portfolio is quite extensive, it began as a small, manageable strategy to contain cost and avoid large budget deficits as the result of HMO failures. The following factors—accelerators and barriers—have either aided or impeded NCH in developing a comprehensive population health strategy and becoming an organization focusing on population health and prevention.

Accelerators

Risk Tolerance and Link to Mission

In some ways, risk tolerance was built into the fabric of NCH from the beginning. NCH’s mission has always been to care for children regardless of their ability to pay and, according to Allen, the hospital has always gone to extremes to demonstrate this commitment. NCH leadership also committed to building and maintaining a culture of risk tolerance at all levels of the organization. This history of risk tolerance positioned the system to be a natural ally and partner for the state in its effort to transform Medicaid, and set the stage for addressing the social determinants of health.

The state of Ohio, independently of NCH, chose to enroll Medicaid beneficiaries into managed care on a mandatory basis. As a result of this decision and because of their own history with risk-bearing contracts, NCH was able to negotiate risk-bearing arrangements with all the Medicaid MCOs and work with the state to operate as an intermediary insurance organization.

Achieve a Strong Financial Position

To successfully take on risk and develop a population health model that provides nonclinical interventions with benefits and return on investment achievable only in the long term, and smaller short-term returns, an ACO or MCO must establish a strong financial position. According to Robinson,

“An organization’s financial position will be a key determinant of how aggressively it can take on risk and/or invest in moving upstream into broader-based population health initiatives. Organizations that have a large reach in their geographic areas may find it easier to demonstrate the value of care management and care coordination, and more quickly move upstream. Other organizations may find the process to be more incremental, focusing first on establishing a financially viable risk model. Either way, it requires enormous commitment and conviction.”

Once such a position is achieved and an organization chooses to pursue this path, the value proposition of population health becomes more visible. Under Allen’s and Robinson’s leadership at NCH, the value proposition for population health has been well established for various constituencies. However, they say this requires constant maintenance in the form of thoughtful, nuanced communication and education for physicians and physician practices, even down to the disease level. Successfully communicating the necessary tension between efficiency (care coordination, management) and market share (heads in beds) with physician leaders can be difficult but is imperative for success.

A Focus on Long-Term Funding for Population Health and Prevention

NCH applies a long-term funding strategy to its population health portfolio, which provides stability in the community and protects NCH’s investments by ensuring that cost-effective, quality-improving strategies endure. Historically this has meant limited grant money, though NCH leadership is open to grant funding to supplement existing projects if there is a sustainable path out of it. This strategy underwrites all population health funding decisions and is a shared value among NCH and external partners.

Capitation arrangement equals flexibility in spending. The payment arrangement under Ohio’s managed care programs provides a significant amount of flexibility for NCH and PFK to invest funds from both entities to support nonclinical population health activities. NCH reinvests some of its Medicaid managed care savings, as well as philanthropic and operations funding, toward such activities. The funds are allocated to upstream population health activities according to three principles: will it save money, will it help make children healthier, and does it match the strategic plan. Progress is measured continually through a regular review cycle.

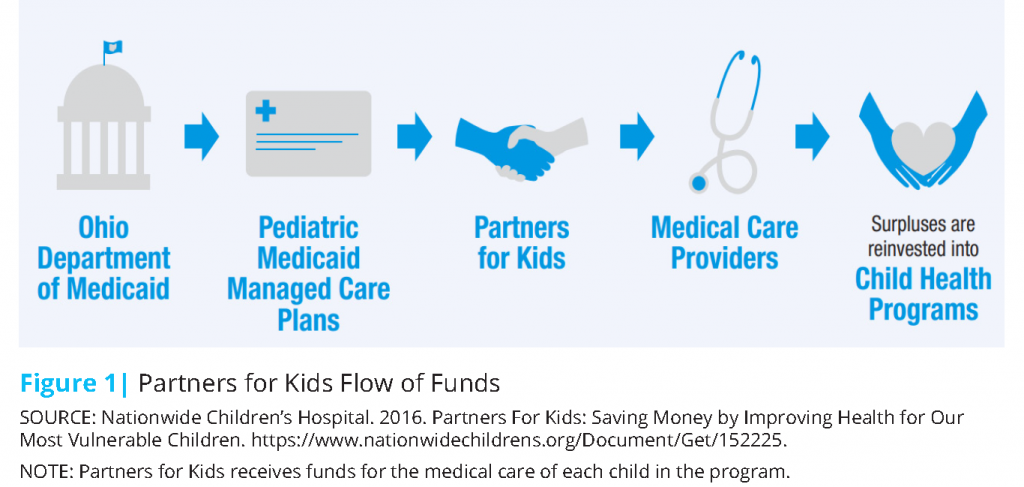

Specifically, funding for PFK flows from the state, through MCO contracts to PFK as illustrated below (Figure 1). Insurers get a capitation payment from the state and retain a percentage for administrative costs such as claims processing, member relations, and management functions. Medical expense payment funds are transferred to PFK which then pays providers for claims, effectively making PFK the payer. PFK has a full risk arrangement and is responsible for any costs over the adjusted per member per month (PMPM) capitation payment, but it can keep all the generated savings that are less than the capitated amount [1]. More specifically, all Medicaid medical expense payments from the state flow through MCOs, which provides direct payment to non-NCH providers (network and nonnetwork) for services. After these claims are paid, the residual funds are transferred to PFK, which pays NCH and affiliated practices through capitated payments. If there are remaining funds in escrow after all claims have been paid, NCH retains those funds and invests a portion on population health activities. If there is a deficit in the escrow account, NCH replaces those funds to balance the account.

It is important to note that PFK’s status as an intermediary insurance organization has unique benefits. Unlike traditional insurance organizations, PFK is not required under law to hold a reserve. However, PFK contractually commits to holding reserves as a function of the payment relationship between PFK and the state’s MCOs. PFK’s reserves are, in turn, applied toward the MCO’s statutory reserve requirements.

Strong partnerships and blended funding streams. NCH understood early on that it could not do this alone; long-term funding sources from outside the health system are critical as well. Aside from PFK savings (Medicaid funds) and NCH funds, population health activities are funded through partnerships and blended funding streams that are not managed directly by NCH or PFK. NCH has intentionally sought out partnerships with local organizations that are prepared to provide financial and executive leadership on joint projects. These organizations are deeply rooted in the community and are committed to long-term investment as well. In NCH’s case, some of these external funding streams include the City of Columbus, United Way funding, state financing (tax credit) dollars, and matched funding by various philanthropic partners located in the community.

Buy-In: Executive Team and Board of Directors

Buy-in at the executive and board level is imperative to success, as no significant investment or change of strategic direction is possible without it. The process to gain buy-in is incremental, project-initiated, and grows over time as success is demonstrated. For NCH, a strong financial position and a proof of concept were established, later developing into a strategic initiative. Hospital leadership also worked intentionally to make the board comfortable with the volatility inherent in risk contracting. Conversations about expanding to upstream interventions began in 2004, setting the stage for an inflection point in 2008.

After a few years of success with the ACO, the board challenged the hospital to address the disparity between clinical outcomes and community outcomes. NCH boasts first-in-class clinical outcomes and is nationally ranked in multiple specialties, but the infant mortality rate and prevalence of behavioral health conditions in Columbus, as two examples, were quite high. The board, comprised largely of local business leaders, expressed concern about the health of the community as an economic challenge—an unhealthy community produces an unstable workforce—and charged the hospital to take accountability.

The CEO, Steve Allen, was also interested in a legacy project that would build a better future for Columbus and potentially contribute to solving larger problems within the health care industry. With the board’s interest in economic improvement and the CEO’s interest in building a better future for Columbus, internal advocates crafted a strategic plan for population health.

Internal champions—the business case. To move the executive team and board of directors in the direction of nonclinical population health investment, there needed to be a strong case and a concrete plan. Internal champions such as Kelly Kelleher, director of the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice and vice president of health services research at the Research Institute at NCH, and Tim Robinson, the hospital CFO, worked with public health experts to develop a nontraditional population health model. This plan included population health intervention and cost-reduction elements as part of the business case.

In addition, the combination of risk (330,000 lives) and geographic concentration (95 percent of those lives reside in the community) presented a clear case for potential return on investment by way of cost savings and improved outcomes in the long term. For example, infant mortality was targeted as a high cost to PFK and requiring inordinate resources for NCH, as neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) demands grew. Addressing the social causes of premature births could help lower the infant mortality rate, which would reduce the cost burden on NCH and benefit the community at large. It was also a priority for city government. Once the plan was developed, Jessie Cannon, director of community wellness initiatives at NCH, administers the plan and ensures that the portfolio of projects is executed. Without such a “quarterback,” the work would not be accomplished.

The moral and political case. Some forms of return on investment cannot be calculated on a balance sheet; rather, they are returned as moral and political capital. In developing a population health plan, NCH intentionally aligned proposed projects with citywide initiatives led by the Columbus mayor’s office. Executive leadership and members of the board realized that, by doing the right thing for the community, they could build symbiotic relationships with community leaders in both government and non-government sectors. With that moral and political capital, NCH built relationships that led to the partnerships they enjoy today. It is these partnerships that have made and continue to make NCH’s population health model such a success.

NCH executive leadership also worked to gain buy-in from clinical leadership by empowering physicians to do the “right thing.” Allen noted NCH’s doctors were already committed to providing the best care for children, so it was a matter of making it easier to do just that. He said doctors “pursue medicine to alleviate the suffering of patients. It is gratifying to align incentives while minimizing the impact of disease.” Robinson also notes that establishing a robust data infrastructure was critical in allowing physicians to “see” what the right thing is. A commitment to the NCH strategy became part of the organization’s physician recruitment strategy as well.

Portfolio Approach to Population Health

An organized approach to population health improvement provides clarity in direction, alignment and synergy between initiatives, and strategic investment of funds. Early on, NCH found that many well-intended physicians were running informal, community-focused projects throughout the organization with no central alignment, accountability, or measurement. Moreover, many projects were not using evidence-based practices, were not monitoring results, and were not using quality improvement methods. After the launch of PFK, an internal effort was initiated to collect these various projects and move them into a single portfolio for more effective management and growth, which included a coordinated approach to funding acquisition. This not only allowed innovation and scaling of interventions that work, but it also positioned NCH to look outside its clinical walls and participate in community-facing initiatives that served the needs of families living on Columbus’s South Side.

NCH then expanded that portfolio to include the population health interventions it is now known for. Using the SMART Aims methodology, the team develops a set of aims or objectives that direct the overall population health strategy. Within those aims, a set of proposed interventions are offered, and from those offerings, two or three are chosen for further exploration and development. Once those are chosen, staff resources are dedicated to developing specific program strategies and predicting the return on investment for NCH. In Allen’s words,

“The overall direction of the organization is developed through our strategic planning process. We scan

the horizon, imagine the future, and determine the programs, people and resources needed to realize our aspirations.”

Community-Centered Plan

NCH targeted community needs when developing its strategy, and it relied on established community activists to catalyze many of the initiatives. Recognizing that providing services that residents want and need was imperative, NCH and partners worked to ensure alignment between community needs and joint investments. This is not synonymous with, though may be informed by, a community needs assessment.

The process of assessing community needs is continuous as community needs change over time. The city of Columbus routinely conducts assessments and NCH conducts surveys and focus groups through the Kirwin Institute. NCH and partners also engage community groups that have been assembled as part of various population health efforts (see Appendix A) to keep a finger on the pulse of community needs. NCH believes this is a “forever activity.”

According to NCH, these various surveys and assessments all come to the same general conclusions: residents of the South Side, an area comprising nine high-risk neighborhoods in immediate proximity to NCH, state that the overwhelming need of families was safety, followed by affordable and stable housing.

Therefore a network of partners and activists—jointly led by Reverend John Edgar of Community Development for All People, Erika Clark-Jones from the Columbus mayor’s office and members of NCH’s staff—committed various levels of funding and support for a suite of initiatives to develop the neighborhood by providing housing support, community development resources, workforce development, early care and education, wellness resources, and many other services. For NCH leadership, the commitment to community needs is not a matter of earning credit but rather an opportunity to contribute to a larger movement aimed at improving conditions for all residents of Columbus’s South Side.

NCH Does Not Do Everything: Lead vs. Follow Strategy

NCH’s level of involvement in each activity or initiative is strategic and varies by degree. NCH’s strategic involvement ranges from simply committing start-up funds to fully funding and running programs. When possible, NCH relies on the expertise and competence of its partners to lead or carry out program execution. When a competency is lacking among its partners, NCH may choose to develop that competency internally and play a leading role in program execution. For example, because some aspects of housing competency were lacking among community partners, NCH developed this competency internally and lends staff FTEs (a cost burden) to the community housing initiative, Healthy Homes.

NCH has also leveraged the role of community integrators, both internally and externally. An integrator is defined as “an entity that serves a convening role and works intentionally and systemically across various sectors to achieve improvements in health and well-being [2].” A person can also provide integrator functions. In the case of NCH, internal integrators also served as

population health champions, referenced above. Reverend John Edgar of Community Development for All People (CD4AP) serves as an external integrator, working with various community resources and agencies, including NCH, to develop a network of services and resources for South Side residents. Without these integrators, the web of wraparound community services (see Appendix A for examples) would not be possible.

Importance of Shared Goals, Metrics, and Measurement: A Long-Term Commitment

Working with its partners, PFK codevelops 10-year goals for population health improvement for target neighborhoods. These shared goals coalesce around a place-based strategy and address community needs such as:

- reductions in substandard housing,

- reduction in property and personal crimes,

- school readiness and graduation rates,

- premature and teen births,

- hospital employment of neighborhood residents,

- neighborhood watch,

- school-based health services, and

- PAX Good Behavior Game implementation (see Appendix A).

In many cases, community partners are able to make progress on their own internal goals as a result of these shared community goals, presenting a compelling case for partnership. For example, schools receive funding per pupil, per seat, per day; by keeping children healthy through physical and behavioral health support, they remain in school and the school receives maximum funding.

Once developed and agreed upon, the slate of 10-year goals is presented to NCH’s board of directors for critique, feedback, and approval. Internal advocates serve a translating role between community partners and the board.

Demonstrating internal progress is key: the value of data. While shared goals are instrumental to larger success, maintaining internal support is equally imperative. The ability to demonstrate progress on internal clinical and population management goals underscores the value of community investment, linking community interventions to clinical outcomes over time. One example of the clinic-to-community connection is PFK’s infant mortality metric that aims to reduce premature births and lower the infant mortality rate. Achieving a lower premature birth rate and infant mortality rate not only results in healthier patients but also reduces NICU costs for PFK. Demonstrating such a significant improvement in the patient population and the overall financial standing of the organization can provide strong justification for continued or expanded investment.

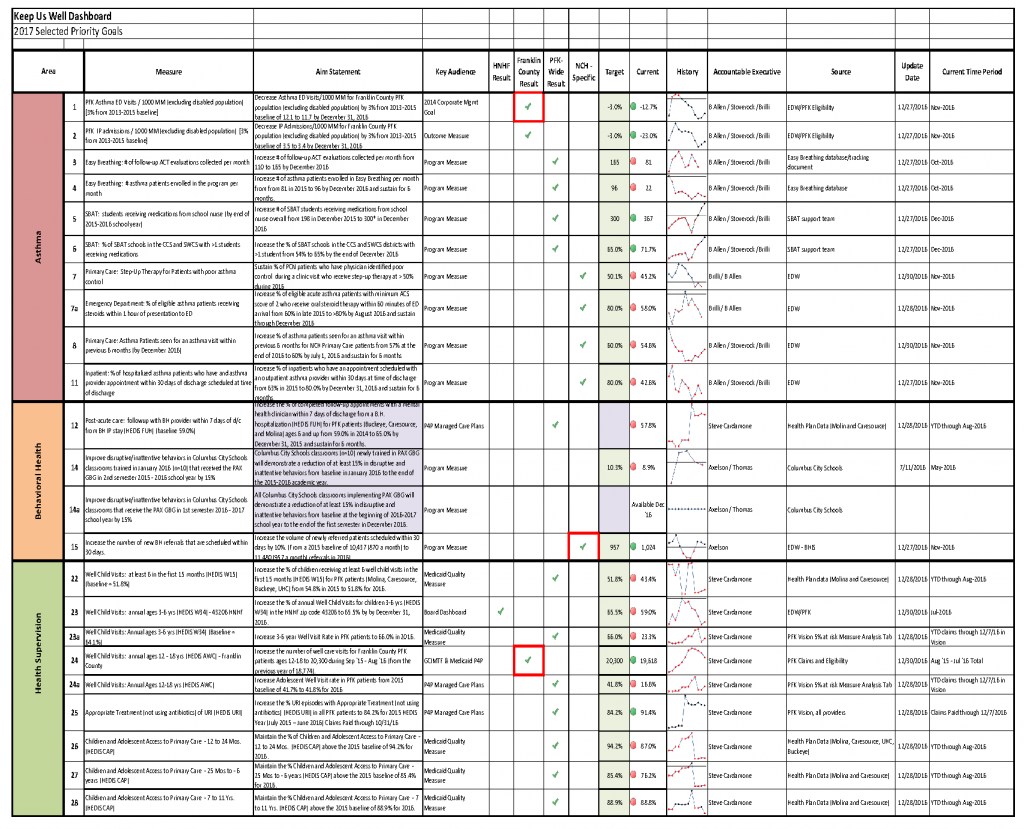

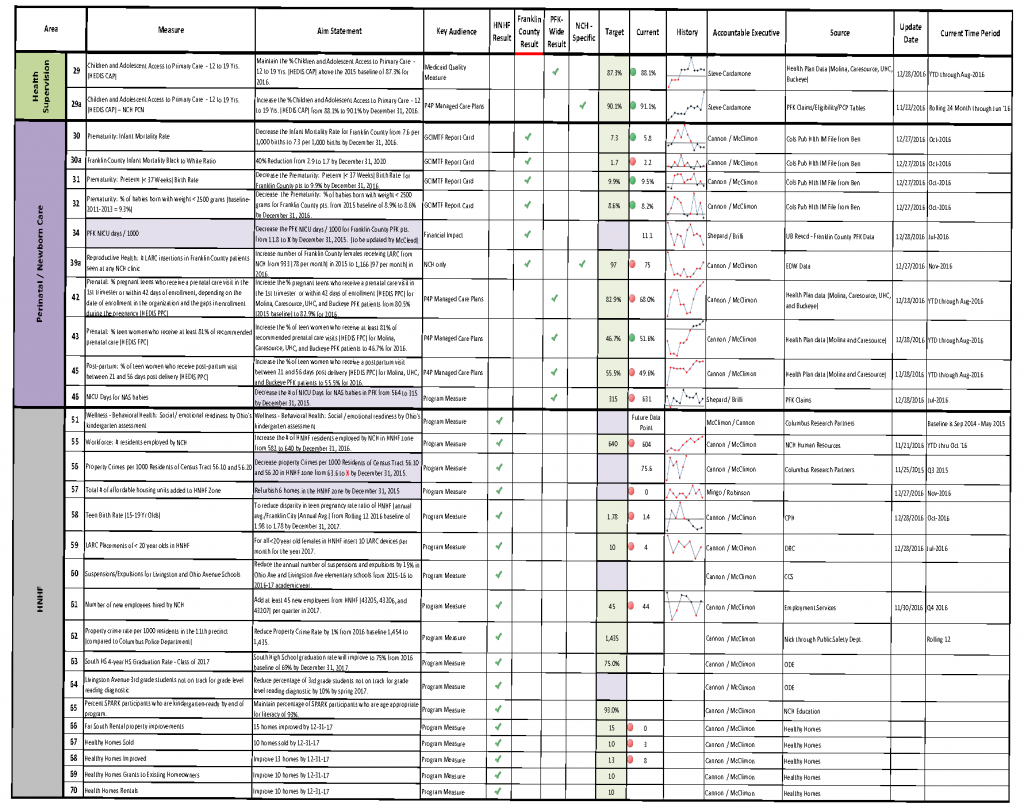

To track progress, PFK uses a variety of metrics, some of which reflect shared community goals. Some general categories include: keep me well, keep me safe, navigate my care, and cure me. Each year, it has a wellness report card with 40 measures including:

- Metrics incentivized by the MCO

- Core pediatric measures (immunization, well-child visits)

- Specific areas of focus (e.g., reducing gastrostomy tube use)

- Neighborhood metrics, such as housing, readiness for school, crime, graduation rates, and teen pregnancy. Each year PFK focuses on three metrics.

Two dashboards are employed to track progress, one for internal metrics and one for shared external metrics (see attached example in Appendix B). These dashboards provide examples of high-priority metrics for PFK and community stakeholders, and indicate progress on each shared goal. This approach may prove useful to other ACOs and MCOs as they plan and track their population health strategy goals.

A cost analysis found that from 2008 to 2013, PFK’s PMPM costs were consistently lower than other Ohio Medicaid MCOs as well as the state’s Medicaid fee-for-service program [3]. During this time period, PMPM costs for PFK grew at a rate of $2.40 per year; managed care plans grew at a rate of $6.47 per year, and fee-for-service Medicaid grew at a rate of $16.15 per year [4].

Barriers

Working Outside Areas of Competency

As NCH expanded its services to include population health activities in the community, they stepped outside the bounds of traditional competencies. The hospital did not have experience in many of the nonclinical interventions it now engages in, and had to cede some control to community partners. It was imperative that NCH chose the right partners who knew the community and were established as trusted leaders.

Perceived Threat to Social Services Agencies

When large organizations step into roles typically held by social services agencies, those agencies’ survival may become threatened. The challenge for NCH was to become a partner and add to the good work already being done, not to take over and adversely affect small agencies that often operate on very slim margins.

NCH had to engage ambassadors from previous projects to vouch for them as a trustworthy partner. There was sometimes a courting period where NCH delivered a benefit to the agency at no cost. Finally, NCH had to prove over and over that they were there to support the community and those social service agencies, and were committed to doing so for the long term.

Data Transparency and Data Sharing

NCH, like most hospitals, has a very robust data infrastructure that allows for data collection and sophisticated analysis. However, data transparency became a hurdle early on because many other partners in Columbus did not have the same technology assets or did not collect, analyze, or publish their data. Some partners were wary of sharing their data for fear that poor baseline data would result in community, funding, or political backlash.

To overcome this barrier, NCH had to devise a neutral path to data collection and outcomes measurement. One example is the creation of a virtual repository where partner data could be collected and stored, but was not owned by NCH. In addition, more focus was placed on percent improvement over time rather than plain statistics, and NCH and partners celebrate achievements along the way.

Community Trust

The neighborhood had many years of experience being jilted by grant-funded groups who came into the community for a short period to build a program or an initiative and abandoned them once funding ran out. Though NCH was not responsible for the actions of other organizations, some members of the community were skeptical of the hospital’s commitment. The only way to overcome this barrier was to build trust over time by being consistently present in community meetings, investing directly in community needs and assets, and continually demonstrating the hospital’s commitment to building a better future for Columbus.

Payment Arrangements

NCH has strong relationships with Ohio’s payers, but negotiating payment arrangements can be challenging for any organization. In NCH’s case, one of the greatest barriers they still face in risk contracting is the threat of “premium slide” where demonstrating savings has the adverse effect of lowering payment rates for future contracts. Lower reimbursement rates affect NCH’s revenue and could ultimately affect its ability to invest in nonclinical activities if payment rates were reduced significantly. So far this has not happened, but it remains a potential barrier.

NCH has also found that negotiating upside risk or shared savings arrangements has been a challenge. Currently, NCH’s private market payment arrangements are pay-for-performance arrangements wherein NCH is paid incentives for high performance. In the future, NCH would like to pursue alternative arrangements like shared savings with their private insurance carriers.

Lessons Learned

A number of lessons can be drawn from NCH’s experience of prioritizing partnerships and long-term funding strategies to positively affect population health. The following is a set of strategies MCOs and ACOs should consider as they embark on their own path toward population health improvement:

Speak to Power – Appeal to Internal and External Power Brokers

Understand Internal Leadership Priorities and Passions

Most people have pet issues or passions they deeply care about. For example, a CEO may have a particular interest in drug abuse and suicide prevalence, or nutrition in schools. That information can be useful as an ACO or MCO crafts a strategy to address population health, incorporating issues of interest to its leadership.

Align Aspirations with External Power Brokers

Working with political, business, and community leaders not only ensures alignment and synergy, but also contributes to long-term success. Together, build a community-centered and informed plan that coalesces around shared goals, develops a long-term funding strategy, and provides services that are needed in the community. The goals of a population health strategy—improved outcomes and lower cost—are long-term goals that require years to achieve. Aligning with external power brokers who also have long-term goals can protect an organization’s investment and the community from disruption.

Move from Isolated Projects to Long-Term Strategy

Often, ACOs and MCOs have various, siloed projects aimed at population health improvement, but they do not mutually reinforce their work, nor are they resourced, measured, or aligned in a centralized way. To achieve high-impact population health improvement, ACOs and MCOs should consider a portfolio approach, which leads to organization-wide strategy and buy-in. In the process of portfolio development, ACOs and MCOs should consider the following:

Target Services Needed in the Community

Many well-intentioned projects fail because they do not address the most critical needs in a community. Work with community leaders to gather direct input from community residents and determine priorities using that data. Often, community-wide health disparities illuminate the direst needs.

It is also helpful to develop strong geographic market share. Market share within the community provides a closer connection between community-level interventions and clinical outcomes, for which the organization is at risk. Such a connection can help justify community investment of hospital, ACO, or MCO funds.

Pilot to Strategy: Demonstrate Proof of Concept and Leverage Cost Drivers

Taking on too much too fast can be overwhelming and will likely not produce the intended outcome. Moreover, it is difficult to convince executive and board leadership to take on significant risk without previous experience and demonstration that the population health approach works. Starting small provides an opportunity to establish a strong financial position and deliver proof of concept early on in order to facilitate greater future investment. A good place to start is by targeting high-cost populations and interventions, such as behavioral health patients or premature births, and affecting upstream determinants for those populations and interventions.

Lacking commitment or conviction and moving too slowly can also defeat attempts to move forward on an integrated population health strategy. Gaining buy-in from internal stakeholders and negotiating with payers requires steadfast commitment and deep conviction that population health is the right thing for the community. Building this foundation is critical. There must be an inflection point where an ACO or MCO fully commits to a population health strategy and moves the entire organization in that direction.

A Long-Term Strategy Underwrites All Planning and Execution

To realize a return on investment, an ACO or MCO must be committed to a long-term plan. In the absence of a long-term plan, short-term goals and short-term financial planning potentially undermine the ability to maximize return on investment and may disrupt effective population health initiatives.

Measure Progress

Develop Shared Metrics

Work with community leaders to gather direct input from community residents and determine priorities using that data. Once those priorities are determined, work with community partners to develop a long-term shared plan that includes specific targets or goals. Progress on these metrics can be shared with internal and external stakeholders and bolster the case for continued or expanded investment in population health.

Develop a Process or Set of Tools to Track Progress

Implementing community dashboards can help ensure all stakeholders are on the same page and driving toward the same goals. Celebrating success is also a useful strategy in keeping partners and stakeholders engaged.

Build Sustainable Relationships

Identify Internal Champions

Internal champions are the driving force behind successful population health strategies. The work is challenging and gradual; champions who are committed to the cause for the long haul provide catalytic energy and continuity for projects. There is also a considerable amount of institutional knowledge that these champions have—leverage it.

Identify and Leverage Integrators

It is not enough to catalyze change; there must be stewards of change who continually stitch together previously disparate resources and expertise among multiple sectors to achieve long-term success. Integrators likely already exist inside your organization and in the greater community, or new or existing partners could evolve into the role of integrator. ACOs and MCOs may also find that more than one internal and external entity or person serves as integrators or provides discreet integrator functions.

Choose the Right Partners

Partnerships are the cornerstone of any successful population health strategy. Capitalizing on existing community assets such as established community activists and extenders (i.e., philanthropic organizations) is a good place to start. Ensure that partners are copilots, not passengers. It will sometime be necessary to rely on their leadership, and ACOs and MCOs must recognize that partners’ goals are as important as their own goals. Where possible, those goals should align. It is likely that the community already has strong activists in faith-based, nonprofit or local government settings. Building a relationship with those activists and recruiting their talent is critical for success. Further, all partners should be prepared to contribute funding and seek additional external funding.

APPENDIX A | Population Health Activities at NCH

Healthy Neighborhoods, Healthy Families (HNHF)

HNHF is a partnership initiative with the City of Columbus, United Way, and Community Development for all People. HNHF programs include affordable housing, health and wellness, education, safe and accessible neighborhoods, workforce development, and economic development. HNHF is supported through a combination of funding mechanisms, including the hospital’s community benefit funds, as well as leveraging of funding through various local and state-based grants, which the hospital has been able to match through its own funds. External funding sources have included:

- Foundations, businesses, the Columbus mayor’s office, and the county commissioner’s office for an infant mortality reduction effort

- Funds from the governor to support the HNHF’s home-visiting program, called START, which focuses on improving reading readiness among children in the surrounding area

- Low-income housing tax credits from the Ohio Finance Authority to support HNHF home revitalization efforts in the local community.

Healthy Homes

A sub initiative of HNHF called Healthy Homes, for which NCH provides funding and support, acquires vacant and abandoned houses and lots in the neighborhood directly south of NCH’s main campus, builds new, affordable homes, provides grant assistance for home repairs, and renovates blighted properties that are converted to rental properties. The majority of home sales are sold at market rate to families or persons at or below 120 percent of the area median income. The home repair program provides funds for repairs such as roofs, porches, energy-efficient window replacement, siding and painting, and landscaping. Rental homes are made available to families or persons at or below 80 percent of the area median income.

Overall, Healthy Homes has created or improved 272 homes with a total financial investment of $18,002,726.

SPARK (Supporting Partnerships to Assure Ready Kids)

HNHF, in collaboration with families, schools, and the community, implements SPARK, an evidence-based kindergarten readiness initiative that provides books, learning activities, supplies, and group-based learning to prepare children for school. SPARK is a home-visiting model that serves 80 preschool children each year, and aims to develop parents as their child’s first and best teacher. NCH’s outcomes show that 89 percent of children participating in SPARK are kindergarten ready, compared to 32 percent before participation—more than 50 percent improvement.

Mobile Care Centers and Care Connection

NCH provides mobile care centers to ensure health care access for children across central Ohio. The mobile care centers travel to schools and communities to provide primary and preventive care, educational services, and Medicaid enrollments assistance to underserved children and their families.

NCH also partners with Columbus City Schools to provide onsite nurse practitioners and behavioral health providers in select locations. Children have access to immunizations, basic illness treatment, well-child checks under physician supervision, and preventive and therapeutic behavioral services. Behavioral health specialists also provide assistance to teachers and school administration in the implementation of the PAX Good Behavior Game, and facilitate the Signs of Suicide (SOS) program.

Other HNHF Initiatives

NCH works closely with community partners to provide support for neighborhood safety programs. These include support for Community Crime Patrol members in the HNHF zone, Block Watch, and neighborhood beautification efforts.

NCH also works to reduce unemployment and poverty in the community by providing work readiness training, career development, experiential learning and directly employing more 450 residents of the HNHF zone, 175 of whom are from targeted zip codes. In addition, NCH (through HNHF) has partnered with the city of Columbus, CD4AP, and the NRP Group to construct and launch the Residences at Career Gateway, a workforce housing community.

The $12 million development will open in 2017, and it will provide 58 one-, two-, and three-bedroom units with varying income eligibility requirements. NCH is the lead workforce training partner. Learn more at http://www.NCHchildrens.org/news-room-articles/community-development-for-all-people-NCH-childrens-hospital-cityof-columbus-and-nrp-group-celebrate-launch-of-the-residences-at-career-gateway-a-12-million-workforce-housing-community?contentid=157610.

PAX Good Behavior Game

The PAX Good Behavior Game is a universal public health approach to prevent psychiatric disorders using strategies to teach self-regulation in the classroom setting. National studies of the PAX approach have revealed short-term outcomes of increased graduation rates, lower special education rates, 0–90 minutes more instructional time, and a decrease in disruptive behaviors. Long-term outcomes show a 50 percent reduction in drug dependence, 35 percent drop in alcohol dependence, 68 percent reduction in tobacco use, 50 percent reduction in suicidal ideation, 32 percent reduction in violent criminal behavior, and a 20 percent increase in youth obtaining a degree.

In Columbus, nearly 90 classrooms or schools have elected to implement PAX. NCH provides funding for PAX trainings and PAX kits, which are used in classrooms implementing PAX, though not every PAX school or classroom is funded by NCH. The mental illness burden on NCH’s service area is significant (about 20 percent prevalence) and PAX is not only effective, but far less expensive than staffing all schools and/or classrooms with behavioral health specialists.

Reeb Avenue Center

NCH provided a significant donation toward the creation of the Reeb Avenue Center, along with many other private donors and public contributors. The Reeb Center is referred to as the “Hub of Hope” on the South Side, and provides community residents with a host of services and community spaces. All of the services and organizations listed below are colocated in the three-floor Reeb Center, as it is intended to be a hub of services for South Side families.

Nutrition:

- Residents can visit the pay-what-you-can South Side Roots Café, a fully functioning restaurant, that serves healthy meals every day, and a free community meal once a week. Café staff includes community residents.

- In concert with the Roots Café, the Mid-Ohio food bank provides affordable, fresh produce and groceries in the South Side Roots Market.

Health:

- CD4AP offers programs to educate families on healthy living and housing stability.

- Eastway Behavioral Healthcare provides mental health services for children and teens.

- Addiction recovery services are provided by Amethyst and House of Hope.

Education:

- South Side Early Learning & Development Center provides early care and education services for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. Services are free for qualifying families. Healthy meals and snacks are provided by the Mid-Ohio Food Bank and prepared in the same kitchen that serves the Roots Café.

- The Boys & Girls Club provides after-school and summer programming for children and teens ages 6 through 19. Services are free to members, and memberships cost $5. NCH staff have volunteered their own time to serve as mentors and chaperones at the Boys & Girls Club.

- Godman Guild provides adult learning and employment services that help residents earn a GED, prepare for college, and find stable employment.

- St. Stephen’s Family-to-Family program provides parent and family education to keep families together.

Workforce Development:

- Digital Works offers technology job training to connect residents with mentors and job opportunities.

- Alvis provides reentry job readiness training and job placement services for residents and families involved in the criminal justice system.

Community Services:

- Lutheran Social Services provides a benefit bank and services for homeless prevention. Through the Stable Families program, case managers are assigned to families at risk of losing their home.

- Ohio State University offers community outreach efforts to educate and assist families with finances, home buying, nutrition, gardening, and more.

- The South Side Neighborhood Pride Center provides access to city services and serves community needs.

APPENDIX B | Measurement Dashboard

References

- Berman, S. 2015. Can accountable care organizations “disrupt” our fragmented child health system? Pediatrics 135(3) e705-e706. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3739

- Nemours. 2012. Integrator Role and Functions in Population Health Improvement Initiatives. Available at: http://www.improvingpopulationhealth.org/Integrator%20role%20and%20functions_FINAL.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Kelleher, K. J., J. Cooper, K. Deans, P. Carr, R. J. Brilli, S. Allen, and W. Gardner. 2015. Cost saving and quality of care in a pediatric accountable care organization. Pediatrics 135(3) e582-e589. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2725

- Nationwide Childrens. 2015. Partners for Kids, Nationwide Childrens Hospital Demonstrate Cost Savings and Quality as Pediatric ACO. Available at: https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/newsroom/news-releases/2015/02/partners-for-kids-nationwide-childrens-hospital-demonstrate-cost-savings-and-quality-as-pediatric (accessed August 24, 2020).