Building Health Literacy and Family Engagement in Head Start Communities: A Case Study

Policy makers, government agencies, and community organizations seeking to improve health outcomes in vulnerable populations are paying increased attention to family engagement and health literacy as key elements of a population health approach. To capitalize on the promise of prevention and create a culture of health, families need a supportive environment that enables them to make informed health decisions and lifestyle choices. Low health literacy is associated with poor health outcomes and is considered a social determinant of health (Healthy People 2020, n.d.b; Rowlands et. al., 2015). To create a culture of health, families with young children need to be engaged as partners and advocates for their children. Family engagement is critical not only to maximizing a child’s academic success but also to fostering positive health outcomes. To accomplish this, sustainable health literacy and family engagement strategies need to be integrated into the core of organizations working to improve health.

The new U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and U.S. Department of Education (DOE) policy statement on family engagement presents 10 principles of effective family engagement that were assembled from an extensive review of the literature (HHS and DOE, 2016). The HHS National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy advocates embedding the principles of health literacy across the educational system and throughout an organization (HHS, 2010; Brach et. al., 2012). In 2016, the Office of Head Start published new program performance standards and for the first time included improving family health literacy (HHS, 2016). The question is how both these concepts can be practically implemented across existing programs, institutions and organizations.

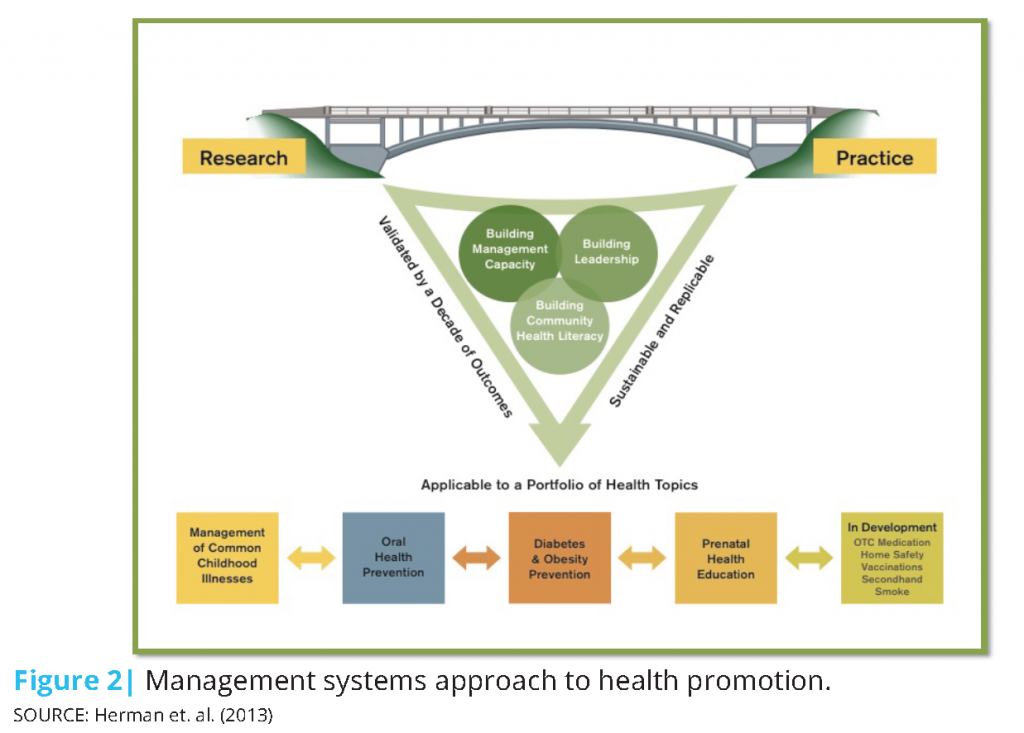

In this paper we present a case study of our work as part of the Health Care Institute (HCI). HCI has used a systems approach to successfully improve health literacy over the past 14 years in culturally diverse, vulnerable communities (UCLA Anderson Health Care Institute, 2016), particularly within Head Start. Using a business management systems approach to health promotion, HCI builds organizational and staff capacity by leveraging many of the principles of family engagement (HHS and DOE, 2016) [1]. We built HCI’s health content based on communities’ needs, and we capitalize on parents’ intrinsic motivation to care for their children’s health. Head Start staff participate in the program as a team, which accords with a key management principle. When staff work together as a team, they align their goals, collaborate on projects, and can serve the children and families in their community more effectively and consistently. Parents build critical self-efficacy by successfully attaining new knowledge and skills, and they surround their children with stronger, more consistent supportive environments at home and at school (Hoover-Dempsey et. al., 2005). Merging two key elements, health literacy and family engagement, into a systems change approach is scalable and replicable and achieves improved outcomes for children, schools, staff, and their families.

The Health Care Institute

HCI uses a comprehensive community-based approach to health promotion for Head Start parents, children, and staff with a portfolio of topics targeting key health issues in prevention. Since HCI’s inception in 2001, we have trained 350 Head Start agencies which have taught over 123,000 parents in Head Start programs nationwide how to appropriately manage everyday childhood illnesses, promote oral health, and reduce obesity. This prevention-focused approach housed within UCLA Anderson’s School of Management has shown consistent, positive outcomes across diverse settings and cultures and has seen a dramatic growth in demand in the last 5 years.

Outcomes

The results show a reduction of emergency room visits, fewer school absences, and increased confidence among parents to make health-related decisions.

The pilot. Our pilot study was conducted from 2003 to 2006. A sample of 9,240 low-income parents of young children were trained on the use of low-health-literacy materials to respond to common childhood illnesses. We used two tools to assess parental use of health care services and parental beliefs about their abilities to care for their children’s health care needs before and after the intervention. Each family completed a pre-intervention and a post-intervention survey, and an additional survey, completed by the home visitor, tracked key outcomes for 3 months prior to the training and for 6 months afterward.

Results from the parents’ assessment surveys showed significant changes in confidence and behavior. Families changed their routine use of emergency room (ER) and clinic visits, first turning to the health resource they were given and trained on for advice. Use of the written health resource increased by 43 percent, and the use of the ER as a first source of help decreased by 75 percent (p<.0001). The tracking survey showed that the average number of emergency room and doctor visits decreased by 58 percent and 41 percent, respectively (p<.001). Furthermore, workdays missed per year by the primary caregiver decreased by 42 percent, and school days missed per year by the child decreased by 29 percent (p < .001) (Herman et. al., 2013).

A reduction in work time lost among parents is important among a population for whom hourly employment is common and directly affects income; job stability is improved as employers see fewer work days missed. The decrease in school days missed is important as more time in classrooms can increase school readiness. All these results remained consistent as we expanded trainings across the country to a variety of settings.

HCI and Obesity Prevention. The HCI has also addressed the obesity epidemic with a three-cohort ecologic model called Eat Healthy, Stay Active!, which trains staff, parents, and children to improve nutrition and increase physical activity (Herman et. al., 2012). The national pilot study involved 6 Head Start agencies in 5 States and demonstrated significant reductions in body mass index (BMI) among parents, staff, and children, and a decrease in the proportion of obese children (30 percent to 21 percent, P < .001) and adults (45 percent to 40 percent, P < .001) over 6 months. We saw increased nutrition knowledge, positive nutrition-related behavior changes among participants, and a significant increase in the frequency of physical activity (Herman and Jackson, 2010). Parents took various actions to change the food served at school based on the new information, staff began walking during lunch with pedometers, and young children begged to do extra loops around the athletic fields!

HCI and Oral Health. Similarly, we piloted our oral health module in the Czech Republic with some UCLA Anderson MBA students, which led to improved oral hygiene practices after the training, as well as a 50 percent reduction in plaque index levels (Herman, 2011). Ongoing qualitative research indicates that parents feel empowered, confident, and engaged and leave the training with more knowledge. They demonstrate they have learned new ways to take care of their children’s oral health needs and establish good oral hygiene habits, show a gain in self-efficacy towards intervening in their child’s health, and gain access to health information they don’t typically have access to. Head Start staff report that they feel the training gave them tools to deliver better services to parents and, most importantly, that they feel engaged by the life-changing impact they have on children and families.

The HCI approach has been implemented in diverse settings including rural Mississippi within weeks of the devastating hurricane Katrina, and the agency there continues to actively use the HCI approach in health for their families to present. Diverse cultures including Native American communities have had similar positive results.

A Management Systems Approach

Head Start, a federal early childhood development program for low-income families, has long recognized the relationship between school readiness and health. When it was founded in 1965 it required comprehensive services for families, including requirements that its grantees offer families services such as health screenings, health education programs, and referrals to health care providers. However, a survey done by Herman in 2003 found that many of the health education programs offered by Head Start agencies were poorly attended and that the information was poorly understood by parents. HCI responded to these problems by developing a structured framework for health promotion focused on building leadership capacity within Head Start agencies and providing culturally adapted, low-literacy materials on health prevention topics. Engaging in cross-disciplinary innovation, HCI borrowed strategies and tactics from the business sector and applied management principles to capacity building and health promotion. The measurement of results and the application of continuous quality improvement was incorporated into the work of HCI from the beginning.

HCI trains Head Start agencies to plan, implement, and deliver low-literacy health education programs in a fun, interactive format focused on building family and community buy-in from the start. With a primary focus on improving health literacy for parents and for staff, HCI simultaneously builds Head Start management capacity, organizational leadership, staff and family engagement, and parental self-efficacy in order to address health disparities at the individual, family, organizational and community levels.

Health Literacy

We have set an ambitious goal of reaching 1 million underserved, low-income Head Start families of various cultures through HCI. Using a population health approach, we work closely with the Office of Head Start and design our work to closely align with Head Start as the main organization for dissemination. According to the literature, a population health approach focuses on improving the health of an entire population through policy, organizational and environmental changes, health education, and comprehensive health promotion programs (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012). It considers the health of a population over the life course and takes a systems change perspective, acknowledging the interrelated conditions and factors that influence people’s health and behaviors. Recognizing the upstream determinants of health in the vulnerable Head Start population, HCI incorporates a population health approach in its focus on prevention, the social determinants of health, and comprehensive health promotion for Head Start staff and families. It incorporates nutrition education and physical activity into its curriculum, encourages family participation and organizational change, emphasizes repetition and follow-up, and includes incentive systems to build engagement. It values continuous improvement and uses feedback from staff and families to modify its program.

Health literacy is a critical and necessary asset with which to improve health among marginalized and disadvantaged populations (Hasnain-Wynia and Wolf, 2010; HHS, n.d.; Nutbeam, 2000). Healthy People 2010 defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (HHS, 2000). The U.S. Department of Education estimates that 9 out of 10 adults have difficulty using available health information at health care facilities, retail outlets, in the media, and within the community (Kutner et. al., 2006). Children of parents with low health literacy have worse health behaviors and health outcomes than children of parents with high health literacy, as parents with low health literacy often have less knowledge and engage in fewer health-promoting behaviors for themselves and their children (Dewalt and Hink, 2009). Targeted interventions aimed at increasing parents’ health literacy and teaching them practical skills to engage in healthy lifestyle choices have been shown to be effective (Dewalt and Hink, 2009; Fleary et. al, 2013).

Simply handing out written heath information or providing traditional didactic health education alone is often unsuccessful in fostering health-promoting behaviors (Ferris et al., 2001; WHO, 2003). Consequently, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion has recognized that positive, lasting behavior change requires a multi-dimensional approach (Healthy People 2020, n.d.a). Through qualitative feedback over the years, HCI found that staff engagement led to parents’ engagement. Building parents’ engagement, self-confidence, and the knowledge needed to engage in health-promoting behaviors were key to fostering knowledge gain and ultimately behavior change. With this understanding, HCI’s training was redesigned to strengthen its emphasis on building staff and family engagement. Head Start staff, as is the case with the general population, often had their own health literacy limitations, which restricted their ability to share accurate health information with families. In response to these findings, HCI designed a train-the-trainer approach using UCLA faculty to train teams of staff from Head Start agencies on management systems such as project planning, implementation, and marketing as well as on health education topics. The approach incorporates the socio-ecological model of health promotion as well as organizational theory and management systems from the business world. The socio-ecological model adopts a systems approach in order to highlight multiple spheres of influence on an individual’s health, including individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy factors (Glanz and Bishop, 2010). Interventions that collectively address as many spheres as possible are used to reduce health disparities and outcomes. Additionally, a management systems approach builds an organization’s human capital, operational efficiency, market strategy, and financial performance.

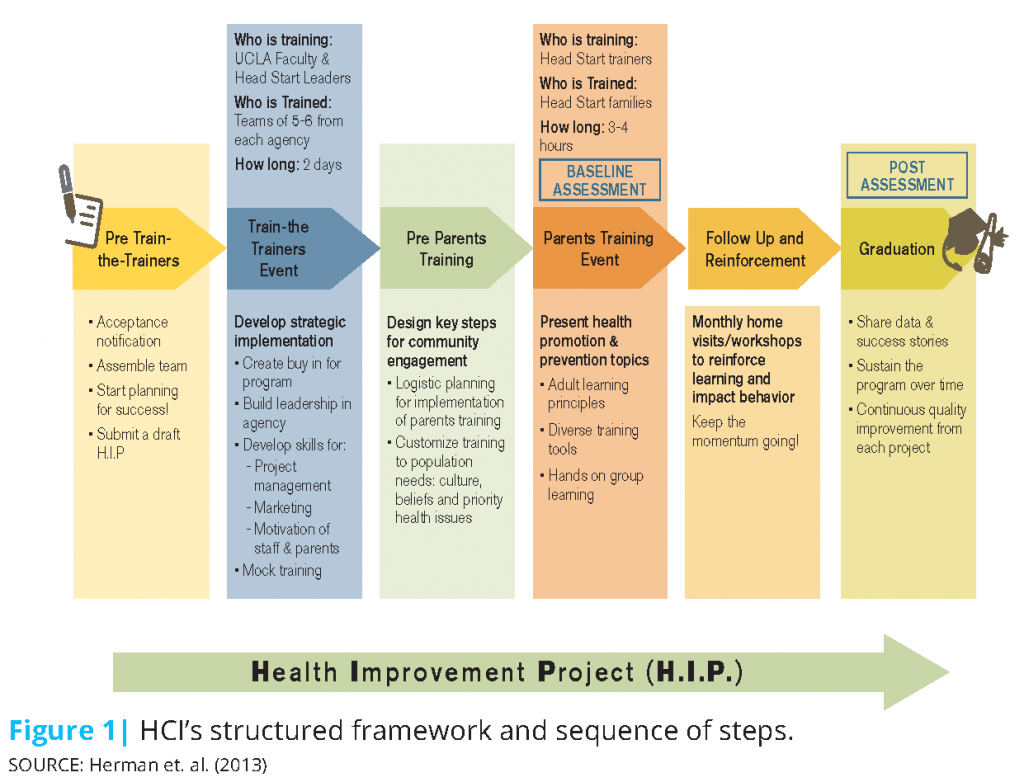

The program’s structural framework and basic sequence of events is depicted in Figure 1 and described in more detail elsewhere (Herman et. al., 2013). Head Start agencies send a team of staff members to the core training; the team structure creates organizational buy-in and the accountability to share lessons learned and creates a structure for retaining this institutional knowledge. Teams are encouraged to identify their health education priorities and organizational capacity for implementation prior to attending the training. During the core 2-day training, participants learn business content such as strategic planning, project management, financial accountability and budgeting, marketing principles and targeted messaging, parent and staff motivation, staff wellness, and community relations. The program guides staff through the process of setting up health literacy workshops for parents, identifying and removing barriers to attendance, and specifically outlining goals, objectives, and realistic timelines through what we call the Health Improvement Project (H.I.P.). The H.I.P is an HCI-designed tool and systematic process for project planning, implementation, and management that agencies can continue to use to plan future health education programs for families.

After the core training is completed, each Head Start agency is required (and has previously committed) to implement a health literacy workshop for parents customized to the needs of its local community. During the core training, Head Start staff are exposed to a mock parent workshop that allows them to visualize how to implement their own health workshops for parents. They identify opportunities to incorporate their own creativity and adaptations for the parent workshops. Staff are also exposed during this mock parent workshop to the importance of family engagement and peer-to-peer interaction. HCI provides ongoing technical support and coaching, a stipend, and low-literacy health education materials to use in these parent workshops. It also conducts motivational webinars and regular check-ins to ensure that agencies remain on track. The methodology focuses on health literacy in order to build self-efficacy, to increase family self-care and preventive health behaviors, and to enhance parents’ ability to communicate with providers about their children’s health. Through the health workshops, families connect with each other for social support, build deeper relationships with staff, and thus build family engagement. Engaged parents are eager and more confident to absorb and act on health information. They begin to attend additional workshops and volunteer in planning such workshops.

Once teams complete the core training, implementation, and data collection, they are eligible to participate in other preventive health modules. Managing common childhood illnesses is the preferred first module because it is a topic of universal concern for parents with young children. Agencies can receive subsequent training on additional modules, including oral health, obesity prevention, home safety, over-the-counter medications, vaccines, prenatal health education, sun safety, and secondhand smoke avoidance.

Family engagement is fostered through a comprehensive program design that values bi-directional dialogue, appreciation, incentives, and continuous improvement.

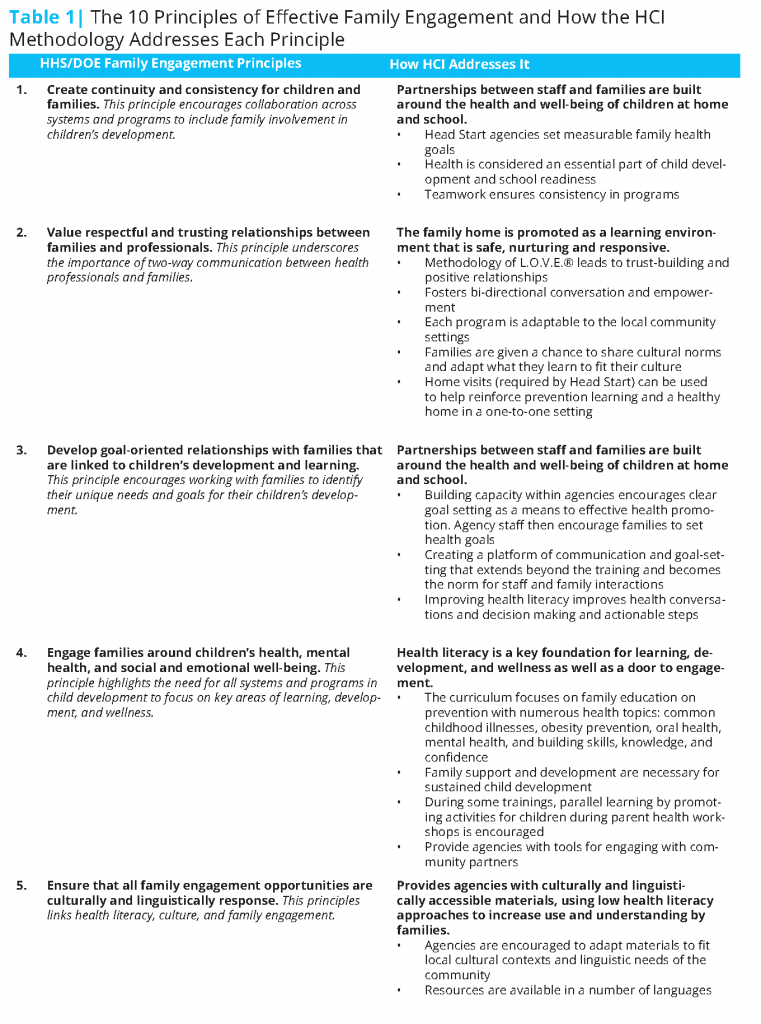

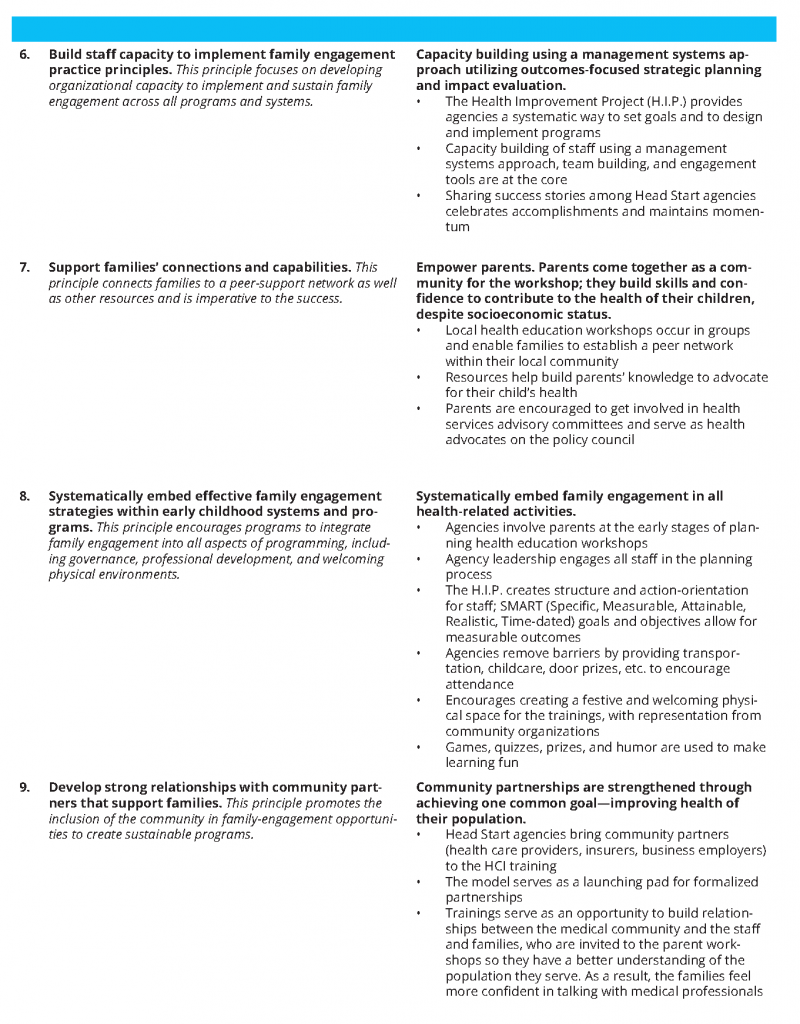

In their recently released policy statement on family engagement, the HHS and DOE define family engagement as the “systematic inclusion of families in activities and programs that promote children’s development, learning, and wellness, including in the planning, development, and evaluation of such activities, programs, and systems” (HHS and DOE, 2016). In other words, families must not only be participants but also be considered “essential partners” in promoting children’s learning, development, health, and well-being. In recognition of the critical role of family engagement in children’s socio-emotional, academic, intellectual, and health-related achievements, HHS and DOE developed frameworks to guide all departments and community-based childhood systems and programs in implementing effective family engagement. In doing so, HHS and DOE conducted extensive literature reviews to identify 10 principles of practice necessary for effective family engagement. The 10 principles, along with a brief description of how HCI addresses each one, are provided in Table 1. A few are highlighted in more detail in the following paragraphs.

In reviewing the comprehensive nature of the 10 principles of family engagement, it is easy to see that a multipronged approach is needed to create staff and family engagement across programs. Engagement then becomes a foundation for shaping the culture of an agency. HCI fosters engagement through a combination of goal-setting, sharing of successes, building trusting relationships, creating a culture of L.O.V.E.® (a methodology that emphasizes listening, observing, valuing, and encouraging in order to create staff engagement), studying data as a means of continuous improvement, leveraging community partnerships, and using linguistically and culturally appropriate low-literacy health education materials.

The programs build staff and family engagement throughout the process by providing health-related incentives (free thermometers, measuring spoons, first-aid kits, etc.) to staff and families to encourage attendance and active participation at the core training (staff) or health workshops (families). Staff receive praise and appreciation from management, and the families who attend receive certificates of completion; both groups highly value their enticements.

Value respectful and trusting relationships between families and professionals (Principle #2)

At the staff training, management recognizes achievements and creates staff enthusiasm for implementing the health literacy parent workshops (which requires extra commitment and work) by reminding the staff of how this provides a connection with the organization’s mission. Past participants have often cited the workshop as a crucial opportunity for creating relationships with parents. Families in Head Start may experience low self-esteem and low self-efficacy and may feel isolated and voiceless in dealings with institutionalized systems of health care. When parents feel Head Start staff have their best interests at heart, they are more likely to engage in learning from staff how best to promote their family’s health. When staff feel they are having a positive impact on families’ lives, they are re-energized. HCI also encourages two-way dialogue between staff and parents. The health literacy workshops for parents start with a discussion between staff and parents about different parenting practices at home, allowing parents a chance to share their cultural context in promoting their children’s health. Creating this time for interaction makes a space for safe learning and allows parents to see staff as partners in their child’s health rather than authorities.

The principles of L.O.V.E.® are part of HCI’s staff engagement strategy. Listening is critical to the success of creating an organizational culture that supports the engagement of parents, staff, and the community. Without listening, messages can be misunderstood and create disorder within an agency or program. Listening is the ability to accurately receive and interpret messages and is key to an individual feeling “heard” and “cared about.” Observations allow staff to learn about others and how to interact with each other in different work environments. Observational learning acknowledges something or someone as being important and allows people to emulate positive behavior. The more employees feel important, the more likely they are to take care of the parents and families they serve. Valuing staff for the important roles they have in helping families reach their potential brings job satisfaction and higher performance to the workplace as well as better outcomes for the families. Encouraging solidifies the “culture of engagement in Head Start.” Encouragement sets a tone that makes work more appealing and optimistic that things can be accomplished. When work becomes more appealing and valued, interactions among staff and with families and the communities become more meaningful. Once demonstrated, staff use L.O.V.E.® to engage with the families they serve during health workshops and beyond. In this way, the health workshops create a safe space in which parents can explore how best to address their child’s health needs.

Organizational capacity building (Principle #6)

At the organizational level, a structured framework is used to build leadership and management capacity within Head Start agencies. The process starts with fostering staff engagement and buy-in. As stated earlier, prior to attending the basic training, the Head Start leadership team has identified health education as a priority for its community and assessed the organizational capacity of its agency to implement the HCI methodology. With guidance from HCI staff, the team learns strategic management principles and develops a strategic plan through the systematic H.I.P. process. Through H.I.P., participants learn to identify goals, objectives, action steps, and desired outcomes and to develop timelines and an evaluation plan. While learning how to implement health literacy workshops for parents, agencies gain the tools to build collaborative teams and systematically plan, implement, and evaluate any future programs. They learn to conduct organizational analyses in order to understand their agency’s strengths and weaknesses, which aids in goal setting to achieve long-term organizational viability.

The intervention with Head Start agencies is three-pronged, as indicated in Figure 2, and helps create the capacity within agencies to implement a wide range of health-promotion programs for local families. The members of the Head Start leadership team build management and leadership capacity and learn how to study their community to design targeted programs. Participants learn the theory of motivation, workplace personality styles, and targeted messaging, which they use to motivate their staff when organizing health promotion workshops and to motivate parents to attend and actively contribute to health literacy trainings.

Systematically embed effective family engagement strategies within early childhood systems and programs (Principle #8); ensure that all family engagement opportunities are culturally and linguistically responsive (Principle #5)

At the individual level, the methodology encourages Head Start staff to use behavior change theory to build self-efficacy, skills, abilities, and knowledge in order to foster engagement among families. Staff are first taught to understand the health needs of the family within a broader context so that they learn to eliminate any barriers parents may face in attending the health workshops. Specifically, agencies are encouraged to: schedule events to match parent schedules; provide transportation, childcare, and translation services for non-English-speaking parents; and provide alternative ways for parents to access the information if they are unable to attend (e.g., home visits). Since HCI encourages agencies to involve all levels of their staff (including janitorial staff and bus drivers) in planning the parent workshops, parents feel a sense of widespread collaboration, enthusiasm, and support from all staff. Once at the training, Head Start staff sit with parents for the welcome meal, which fosters engagement and strengthens relationships. The festive, fun, and interactive environment of the workshops incorporates adult learning principles and is a crucial element in creating a welcoming physical environment. In addition, HCI provides low-literacy and culturally adapted materials so families are not overwhelmed and feel that they can master health concepts and understand the resources they receive. Past participants mention this approach frequently as a key to the program’s success.

Develop strong relationships with community partners that support families (Principle #9)

The longstanding impact of the program within the broader community has repeatedly been demonstrated. As a result of its emphasis on engaging the community in each parent workshop, new partnerships have been forged with medical professionals, educational institutions, businesses, and corporations. Parents learn that they have a place in their community and start to ask for things on behalf of their school and children.

Healthcare and education. As an example, Central Missouri Community Action (CMCA) Head Start has been implementing these methods for over 10 years. A partnership with the University of Missouri School of Nursing has led to regular internships for nursing and public health students with CMCA Head Start annually [2]. These interns help plan and implement health promotion programs at the 22 Head Start and Early Head Start centers that CMCA operates in eight mid-Missouri counties. CMCA agencies benefit from the content expertise that these interns bring, and the interns find the interaction with the community invaluable to their education. A strong partnership with the School of Nursing and the School of Public Health has since led to similar partnerships with the School of Medicine to create training opportunities for medical residents on poverty and health literacy in low-income families. To date, the partnership has educated over 55 medical students through participation in yearlong community service and eight hours in Head Start classrooms and helping train families using HCI’s obesity-prevention curriculum. (Milford et al., 2016) Currently, CMCA is working on developing a training program for dental residents with the dental unit of the local Family Health Center, which is a federally qualified health center.

Corporations. Similarly, CMCA has cultivated loyal and longstanding partnerships with companies that contribute in-kind to CMCA’s initiatives. Walmart contributes money and its in-store gently used bicycles to CMCA’s efforts as part of the obesity-prevention curriculum. In hearing this, State Farm Insurance chose to donate helmets each year to supplement Walmart’s bicycle donations and thus offer safe active transportation options to families and children. In appreciation, CMCA named its State Farm liaison Partner of the Year. In addition, a previous employee of CMCA moved to 3M and brought her dedication to the work of Head Start and HCI to the company. As a result, over the years 3M has granted CMCA over $10,000 along with supplying volunteers and small gifts of cash. For families of Head Start, who seldom receive positive feedback or tokens of appreciation, having useful supplies provided in the form of gifts not only reduces their financial burden, as these are useful health-related items, but also gives them a sense that HCI and Head Start care about and appreciate them.

Continuous improvement and data-driven decision making (Principle #10)

Participants learn data-driven decision making and to demonstrate the value of this in their own practice: each participating Head Start agency receives a detailed and tailored quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the outcomes specific to that agency after it hosts a health literacy workshop for parents. Agency reports show shifts in parents’ attitudes towards common childhood illnesses, in their knowledge about health-promoting behaviors, and in their intentions to engage in positive health decisions for their families. Subsequent monitoring and data collection by the Head Start agency assess changes in school attendance rates and emergency room or doctor’s office visits. HCI analyzes data from pre- and post-workshop parent surveys and presents these findings in graphical form to each grantee. Seeing the impact of their work on local Head Start families has repeatedly proven to be invaluable to staff [3].

The continuous improvement data cycle is depicted schematically in Figure 3. HCI delivers core training and additional health module training to Head Start agencies, and it uses the feedback it receives from agency staff to improve its offerings. Head Start agency staff adapt what they learn during the training to their own local community contexts as they implement a health literacy workshop for parents. HCI coaches them along the way, providing them with an analysis of the pre- and post-workshop parent survey upon completion of the workshop. Head Start staff also receive feedback from parents during home visits when they review material with families. HCI and agencies use this information to update and revise their programs.

Conclusion

This case study underscores the importance and feasibility of family engagement, health literacy, and organizational capacity building in improving health outcomes among Head Start communities. The cross-sectoral methodology combines a population health and socio-ecological approach with management systems from the business sector. The unified approach has improved health promotion and has implications for public health initiatives beyond Head Start. The model could be replicated in other family-centric early childhood centers and public health programs that look at health through a population health lens. With the Office of Head Start’s focus on reducing disparities, the new performance standards’ emphasis on the importance of health literacy and the HHS’s recent policy statement on effective family engagement have created an environment ripe to implement innovative, multidisciplinary solutions to reduce health disparities and improve health equity (Teutsch et al., 2016). In the long run, embedding health literacy and family engagement into organizations and community programs could lead families to use health services more effectively, feel empowered to communicate with providers, and work to bring community partners together on health issues. The HCI approach serves as a model that successfully applies multidisciplinary approaches and builds sustainable systems that solve some of the most salient health challenges in diverse, underserved communities.

Notes

- https://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/earlylearning/files/policy-statement-on-family-engagement.pdf.

- Interview with M. King, Head Start director, Central Missouri Community Action, March 21, 2016.

- Interview with M. King, Head Start director, Central Missouri Community Action, March 21, 2016.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2010). National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC. Available at: https://health.gov/communication/hlactionplan/pdf/Health_Literacy_Action_Plan.pdf (accessed October 07, 2016).

- Dewalt, D. A., and A. Hink. 2009. Health literacy and child health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics 124(Suppl):S265–S274. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1162b

- Ferris, F. D., C. F. Gunten, and L. L. Emanuel. 2001. Knowledge: Insufficient for change. Journal of Palliative Medicine 4(2):145–147. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662101750290164

- Fleary, S., R. W. Heffer, E. L. Mckyer, and A. Taylor. 2013. A parent-focused pilot intervention to increase parent health literacy and healthy lifestyle choices for young children and families. ISRN Family Medicine 2013:1–11. https://doi.org/10.5402/2013/619389

- Glanz, K., and D. B. Bishop. 2010. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health 31(1):399–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604

- Hasnain-Wynia, R., and M. S. Wolf. 2010. Promoting health care equity: Is health literacy a missing link? Health Services Research 45(4):897–903. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01134.x

- Healthy People 2020. n.d.a. Health communication. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2010/document/html/volume1/11healthcom.htm (accessed October 10, 2016).

- Healthy People 2020. n.d.b. Social determinants of health. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed October 7, 2016).

- Herman A. 2011. Pediatric oral health in the Czech Republic: A family health literacy approach. HARC Institute of Medicine Health Literacy Research Conference. Available at: http://impactmap.anderson.ucla.edu/Documents/areas/ctr/jandj/poster_pediatricoralhealthczech.pdf (accessed July 24, 2016).

- Herman, A., and P. Jackson. 2010. Empowering low income parents with skills to reduce excess pediatric emergency room and clinic visits through a tailored low literacy training intervention. Journal of Health Communication 15(8): 895–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2010.522228

- Herman, A., B. B. Nelson, C. Teutsch, and P. J. Chung. 2012. Eat Healthy, Stay Active!: A coordinated intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity among Head Start parents, staff, and children. American Journal of Health Promotion 27(1):E27–E36. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.110412-quan-157

- Herman, A., B. B. Nelson, C. Teutsch, and P. J. Chung. 2013. A structured management approach to implementation of health promotion interventions in Head Start. Preventing Chronic Disease. 10:130015. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.130015

- HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). n.d. Health literacy—Fact sheet: Health literacy and health outcomes. Available at: http://health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/factsliteracy.htm (accessed June 3, 2016).

- HHS. 2000. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: U.S. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2010.htm (accessed August 24, 2020).

- HHS. 2010. National action plan to improve health literacy. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://health.gov/our-work/health-literacy/national-action-plan-improve-health-literacy (accessed August 24, 2020).

- HHS. 2016. Head Start policy and regulations. Available at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/pi/acf-pi-hs-16-04 (accessed October 07, 2016).

- HHS and DOE (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Education). 2016. Policy statement on family engagement from the early years to the early grades. Available at: www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/earlylearning/files/policy-statement-on-family-engagement.pdf (accessed October 07, 2016).

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., J. M. T. Walker, H. M. Sandler, D. Whetsel, C. L. Green, A. S. Wilkins, and K.E. Closson. 2005. Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. Elementary School Journal 106(2):105–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1001400104

- Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93(3):380–383. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.3.380

- Kutner, M. E. Greenberg, Y. Jin, and C. Paulsen. 2006. The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES publication 2006-483. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Milford, E., K. Morrison, C. Teutsch, B. Nelson, A. Herman, M. King, and N. Beucke. 2016. Out of the classroom and into the community: Medical students consolidate learning about health literacy through collaboration with Head Start. BMC Medical Education 16:121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0635-z

- Nutbeam, D. 2000. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International 15(3):259–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

- Public Health Agency of Canada. 2012. What is the population health approach? Available at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/approach-approche/index-eng.php (accessed October 31, 2016).

- Rowlands, G., A. Shaw, S. Jaswal, S. Smith, and T. Harpham. 2015. Health literacy and the social determinants of health: A qualitative model from adult learners. Health Promotion International, September 27 [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav093

- Teutsch, S. M., A. Herman, and C. B. Teutsch. 2016. How a population health approach improves health and reduces disparities: The case of Head Start. Preventing Chronic Diseases 13:150565. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150565.

- UCLA Anderson Health Care Institute. 2016. Improving the health of our communities . . . one family at a time. Available at: www.anderson.ucla.edu/centers/price-center-forentrepreneurship-and-innovation/for-professionals/ health-care-institute (accessed October 30, 2016).

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2003. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who. int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf (accessed October 7, 2010).