Harmonizing Reporting on Potential Conflicts of Interest: A Common Disclosure Process for Health Care and Life Sciences

The Urgent Need for Harmonization

The 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice reported that “patients and the public benefit when physicians and researchers collaborate with pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies to develop products that benefit individual and public health” (p.1). Because, as the report stated, “wide-ranging financial ties to industry may unduly influence professional judgments involving the primary interests and goals of medicine,” the authoring committee also recommended approaches to managing conflicts of interest (COIs), particularly financial relationships, without deterring fruitful scientific collaboration among academics, health care professionals, and industry. In doing so, one concern identified by the committee was the substantial but possibly avoidable burden placed on health care professionals and biomedical researchers by repetitive, overlapping but non-identical, time-consuming procedures and forms required by different organizations for reporting relationships for evaluation of possible COIs (IOM, 2009).

Accurate reporting can identify circumstances in which there exists the possibility of inappropriate influence over patient care, education, or research. As data accumulate about the impact of nondisclosure of relationships, requirements are increasing for individual clinicians and researchers to report their relationships (Blumenthal, 1996; Bodenheimer, 2000; IOM, 2009). These individuals—and, increasingly, students and trainees—are routinely required to provide this information to a variety of organizations with stewardship responsibilities—academic institutions, funders, journals, continuing medical education groups, and more. From a regulatory perspective, in addition to regulations and rules requiring financial disclosures by individuals, (e.g., from the National Institutes of Health [NIH] and the Food and Drug Administration [FDA]), federal law will soon require companies to report their financial relationships with physicians and academic medical centers. The data gathered under the Physician Payment Sunshine Act (Sunshine Act) (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7h[a]) will be made public, increasing the importance of thoroughness and accuracy in disclosure. Finally, as the country moves toward achieving a truly learning health system—one in which research becomes integrated with patient care—a clear understanding of relationships can help ensure the integrity of the scientific process, clinical training, and education while simultaneously expediting adoption of new and innovative tests and treatments.

The current process of disclosure is fragmented and burdensome for clinicians, researchers, students, trainees, and others who are required to report relationships (reporting individuals). The Federal Demonstration Partnership, a group dedicated to reducing the administrative burdens associated with research grants and contracts, estimates that “42% of an American scientist’s time is spent on administrative tasks. Much of that burden comes from redundant reporting and assurance requirements that vary” (Leshner, 2011). (Indicates the percent of time faculty spent on completing administrative work from federally sponsored research, or about 16 percent of their total work-week time. Data from the Faculty Burden Survey Report of the Federal Demonstration Partnership, January 2007.) Considering this waste, and anticipating the growing requirements for disclosure by reporting individuals, the need for a harmonized system becomes urgent and compelling.

The Regulatory Environment

Policies on COI in the health and life sciences have become commonplace, as have efforts to clarify and tighten related stewardship responsibilities. Many public and private organizations require disclosure of relationships by individuals, including federal agencies like NIH, FDA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the National Science Foundation, as well as academic medical centers, scientific journals, purveyors of continuing medical education (CME), and more. Perhaps most relevant to researchers in the health and life sciences, since 1995 the Department of Health and Human Services has required that organizations receiving grants for research from the U.S. Public Health Service make and enforce policies to ensure that relevant financial COIs are identified and managed. Because the details of the policies and procedures have largely been left up to organizations, significant variation exists as to the definition of COI, the reporting policies, and the disclosure requirements for individuals (Cho et al., 2000).

Recently, a number of organizations—notably, NIH and CMS—have initiated changes in their requirements. In 2011, NIH released the Final Rule on Conflict of Interest, which updated the 1995 regulations (NIH, 2011). This included a decrease in the threshold that constitutes a significant financial interest (from $10,000 to $5,000), an expansion of the disclosures that an investigator is required to make to the organization, an increase in the information that organizations must report to the funding agency, a requirement for some public reporting of information, and a program of training for investigators about COI regulations and policies. Notably, the Final Rule indicates that reporting individuals will need to disclose significant financial interests related to their institutional responsibilities.

In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was signed into law, including the physician payment disclosure provisions under Title VI, Section 6002—the Sunshine Act. These provisions require manufacturers whose products are covered by the financing programs of CMS to report gifts and payments made to physicians (CMS proposes that physician be defined by the term used in Social Security Act section 1861(r)) and teaching hospitals, as well as physician and immediate family member ownership interests. Data from reports made annually to CMS by manufacturers will be posted on a publically-available website. The final rule governing the exact nature and format of reporting requirements has not been released as of the publication of this discussion paper, although the proposed rule was made available in December 2011 (CMS, 2011). It is anticipated that the law may add to complexity in reporting, largely due to challenges in reconciling individuals’ reports with those of manufacturers. We anticipate that a harmonized system as described in this paper will relate to the CMS regulations in two ways: first, by providing a platform for physician recordkeeping of interactions, and second, by simplifying the process of review and appeal by physicians and teaching hospitals. Important issues with regard to the intersection of the harmonized system described in this paper and the proposed Sunshine Act definitions, categories, and procedures are outlined in Appendix III.

The Approach to Harmonization

The 2009 IOM report recommended that “national organizations…represent[ing] academic medical centers, other health care providers, and physicians and researchers should convene a broad-based consensus development process to establish a standard content, a standard format, and standard procedures for the disclosure of financial relationships with industry.” This task can be approached in two ways: 1) by standardizing organizational requirements for reporting relationships; or 2) by identifying a standard format, definitions, and harmonized procedure for individuals to use in reporting relationships, as requested in various circumstances. The first approach requires agreement upon modification of multi-organizational regulations and policies, many of which operate with different requirements and circumstances. The second approach—developing a standard format and harmonized procedure for disclosure by individuals, populating the format fields according to individual requirements—is largely technical and, thus, more readily engaged. Here, we take the second approach and describe proposed elements, definitions, format, and common procedures for data entry, storage, and access.

Following the 2009 recommendations, the IOM hosted a multi-stakeholder meeting in July 2011 to discuss approaches to harmonizing the process of reporting relationships for evaluation of possible COI. The goal was to identify key elements necessary to enable a reporting individual to provide data easily, and without repetition, to organizations requesting disclosure of relationships. The approach consisted of careful exploration of regulations and requirements for disclosure and discussion of the needs and preferences of multiple stakeholders. After the meeting, stakeholders were organized into two working groups—Field Definitions and Data Repository and Retrieval—to discuss options for a harmonized process focused on two goals: first, to identify the content and format of a common set of elements with sufficient scope to accommodate reporting needs across a range of organizations; and, second, to describe options for reporting, storage, and retrieval of these elements, along with practical principles and strategies to guide system design and implementation. Specifically excluded from consideration were issues related to thresholds constituting significant relationships or COI, which vary by organization, circumstance, and regulatory requirements in play. Charges to and participants of the two working groups are presented in Appendix I.

The Common Application: A Model for Comparison

In the course of the groups’ discussions, references were made to a practical model from the education sector: the common application for undergraduate college admission (the common app). The mission of the nonprofit membership organization that administers the common app is to provide “reliable services that promote equity, access, and integrity in the college application process” (Common Application, 2011). Students who use the system can submit a completed application, and all supporting materials, to any number of the member institutions. The logistical benefit of the common app to students is a reduced burden of repetitive, time-consuming paperwork. The benefit to institutions is receipt of student data in a standardized, digital format that requires minimal internal expenditures and maintenance. By implementing a harmonized system for disclosure of relationships, we believe individuals and organizations will accrue the same benefits. An important way in which the harmonized system differs from the common app is that, in many cases, students are asked by institutions taking the common app to also complete a supplementary application. We believe that supplementary applications limit the ability to achieve the vision of maximal burden reduction and efficiency. The harmonized system must encompass the full scope of reporting indicated by statute and regulation and most if not all of the reporting currently requested by organizations. A thoughtfully constructed system that meets these needs, allows institutions to filter for information relevant to them, and maintains a nimble updating capacity has the best chance to be broadly accepted by individual and organizational users. (We note that when institutions identify possible COI from submitted reports, they may engage with the individual reporter in an evaluation of the relevance of the relationship—a process which may include more detailed discussion or documentation.)

Goal 1: Common Disclosure Elements and Format

The Field Definitions Working Group was tasked with identifying a set of common elements to accommodate most current and anticipated requirements for disclosure of relationships for evaluation of possible COI. The group reviewed 23 sample disclosure forms made available by participants from across health care sectors (federal agencies, academic institutions, journals, CME providers, and professional organizations). This survey of current requirements revealed substantial differences, including varied directions to reporting individuals, incompletely aligned data elements, differences in response format (e.g., open-ended vs. closed questions), and a range of requirements for inclusion of family members’ relationships with industry. Some elements are legislated or regulated, others are developed locally by institutions and organizations. Harmonization of definitions and requirements, to the extent possible under current regulations and policies, will simplify data collection, storage, maintenance, and retrieval. Harmonization may also improve the accuracy of data and reduce the need for clarification and revision. To this end, we suggest common elements intended to meet the needs of many organizations’ current policies on COI.

Relationships to be Reported

The 2009 IOM report defines COI broadly as “circumstances that create a risk that professional judgments or actions regarding a primary interest will be unduly influenced by a secondary interest.” Primary interests are those related to conducting research, taking care of patients, and providing medical education. Secondary interests are those that relate to an individual’s gain—e.g., financial, professional, political, or interpersonal. The committee recognized that although other relationships might compromise objectivity, financial relationships may be the easiest to measure and track (IOM, 2009). We propose that to meet many current regulatory and organizational requirements, a harmonized system should instruct reporting individuals to disclose relationships, activities, or interactions that may influence—or that give the appearance of potentially influencing—professional judgments or actions.

Relationships of Others to be Reported

The 2009 IOM report does not give specific guidance about which family members’ relationships ought to be disclosed. Current organizational and regulatory policies vary widely. For example, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requires reporting individuals to disclose data related only to themselves, whereas the CMS Sunshine Act provisions require disclosing relationships held by “immediate family members,” extending to those beyond the nuclear family, in the case of physician ownership and investment. Although manufacturers will be required to report these extended relationships to CMS, reporting individuals also will need to track these relationships to ensure accuracy (CMS, 2011; ICMJE, 2009). To meet the requirements of all organizations requesting disclosure statements from reporting individuals (requesting organizations), a harmonized system will need to accommodate reporting for as many different family members as are currently required by organizations.

We note that, with regard to inclusion of data about others’ financial relationships, current requirements for inclusion of extended family members’ data creates a significant, and likely unnecessary burden, on reporting individuals and does not necessarily fulfill the intent of limiting COI. For example, an unmarried individual in a long-term relationship would not usually be required to report the financial relationships of his or her partner. As another example, it seems plausible that an individual estranged from his or her family members might not be unduly influenced by their financial relationships. Furthermore, in some situations, reporting individuals may be unable to obtain the details needed from family members, yet might be held accountable for any inaccuracy of these data. One possible solution to some of these issues is to consider the potential for bias as a product of the closeness of a personal relationship and the magnitude of the financial relationship. For example, equity holdings of a spouse, domestic partner, or child might be considered significant, whereas a cousin or grandparent’s relationship with a manufacturer might only be considered significant if this relationship results in substantial income.

We suggest the following general principles to guide decisions on when, and at what level, to require reporting of family members’ relationships. First, we suggest that reporting individuals should disclose others’ financial relationships if there exists the possibility that the financial relationship will benefit the reporting individual, including if the reporting individual has benefitted in the past. Second, to help ease the burden of disclosure, we also recommend that requesting organizations consider whether the individual reporters can verify the accuracy of others’ relationships—for example, by requiring only those that are a matter of public record. One way to accomplish these two goals would be simply to require disclosure of relationships of the reporting individual’s spouse or domestic partner and dependent children, with expanded disclosure of family financial relationships that may influence professional judgment, and with accommodation for unusual cases, such as with special government employees (SGEs) who advise FDA and are required under federal law (18 U.S.C. 208) to report certain financial interests of individuals and institutions, whose interests are imputed to them regardless of the magnitude of the interest.

Data Elements in Reporting

Several issues present a challenge for harmonization of data elements: terminology is not standardized; individual data elements overlap, as do the categories in which they reside; and many current questions and categories are open-ended. For example, with regard to relationships with publicly traded companies, NIH defines remuneration as “salary and any payment for services not otherwise identified as salary (e.g., consulting fees, honoraria, paid authorship); equity interest includes any stock, stock option, or other ownership interest, as determined through reference to public prices or other reasonable measures of fair market value” (NIH, 2011). In comparison, the ICMJE form for disclosure requests information about “resources that [the author] received, either directly or indirectly (via [his or her] institution)” used to conduct the work presented in the submitted manuscript (ICMJE, 2009). Based on our survey of requirements and disclosure forms, we propose the following general features for a harmonized set of data elements:

- Data elements should be non-duplicative and discrete (non-overlapping).

- Fields should allow the option other, with specification of further details.

- Data elements should be easily and immediately updatable.

- Data elements requested of individuals should be only those that are applicable.

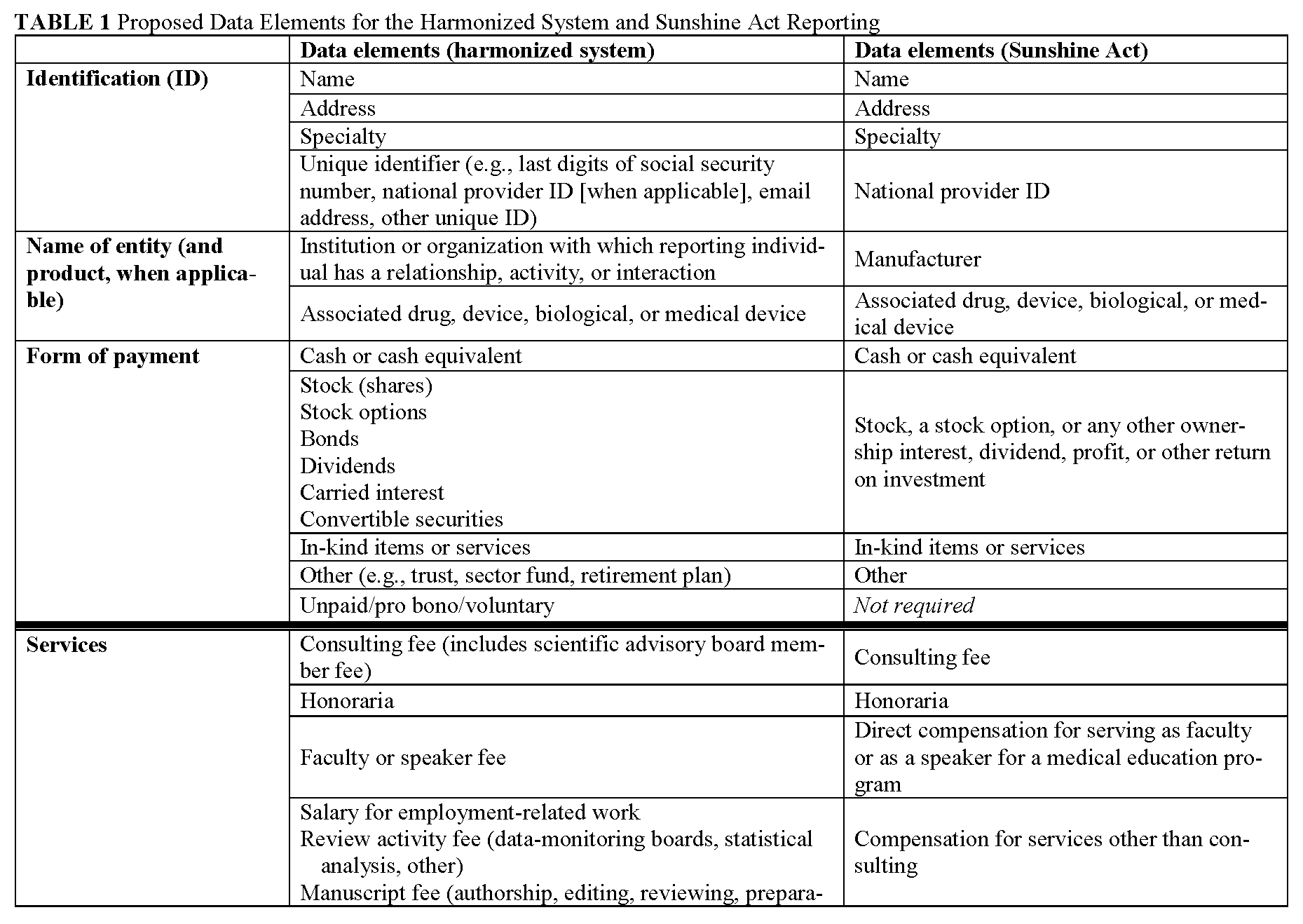

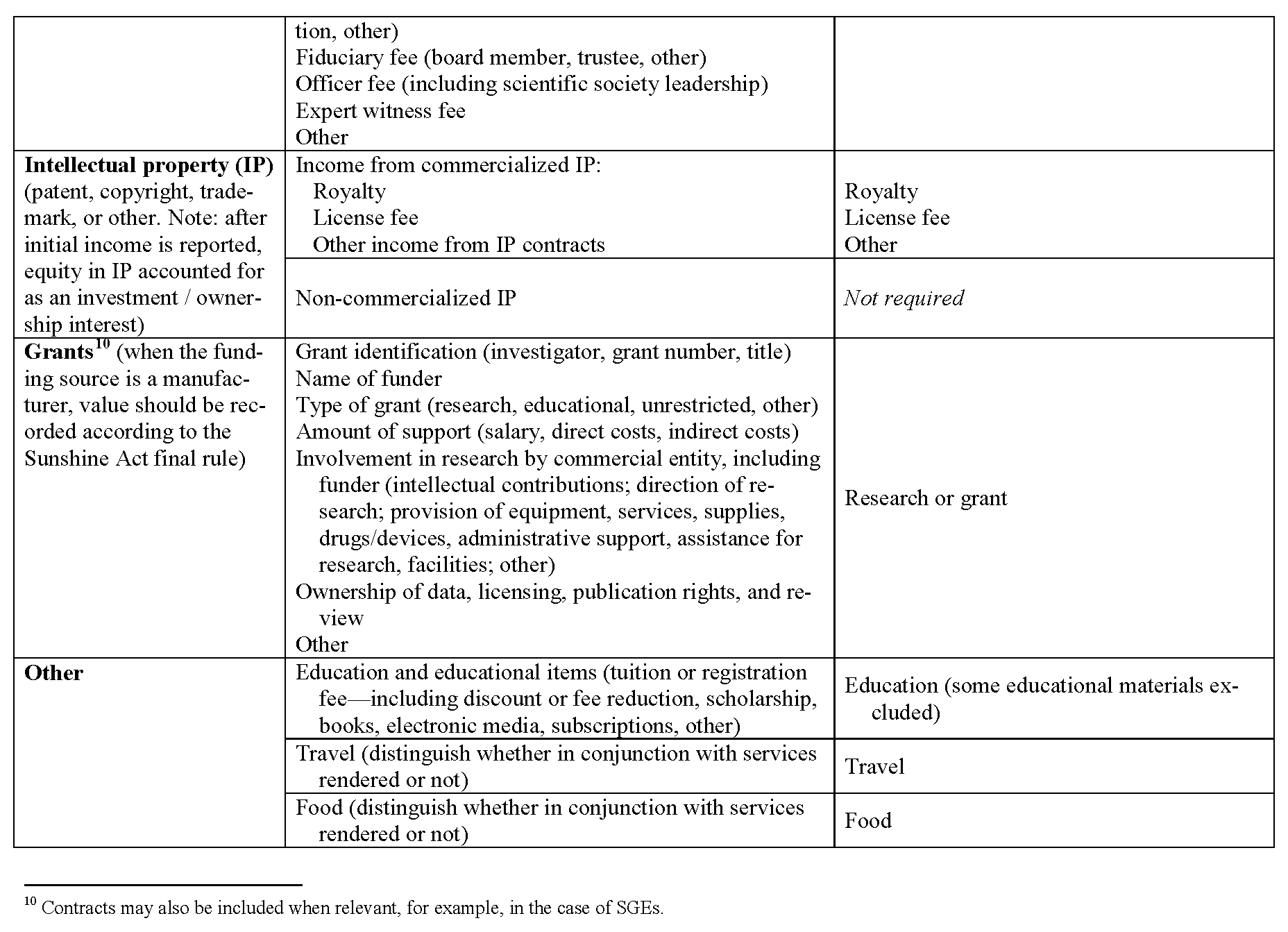

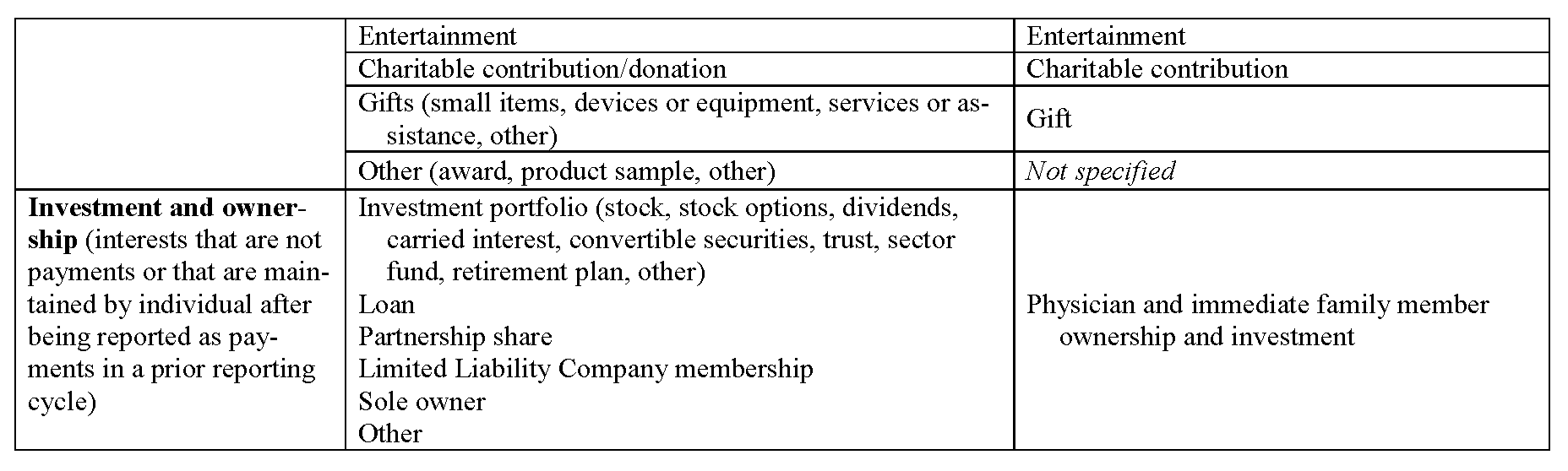

Definitions of common data elements are presented in Appendix II, and a table that lists broad categories of data fields—with reference to the categories contained in the Sunshine Act—is presented in Appendix III. This set includes the overarching categories and data elements common to many requesting organizations and does not attempt to harmonize the determination of when a relationship is significant or constitutes a significant COI. It is important to note that many requesting organizations will require reporting for only a subset of the fields listed. Accordingly, reporting individuals will need to fill out only those data fields relevant to their personal roles and relationships. The process for tailoring the presentation of data fields to the reporting individual is described in the next section.

In addition to the definitions and fields listed in Appendixes II and III, several other parameters should govern the data fields within the harmonized system. First, data elements should be reported separately for each relationship. Second, in conjunction with the anticipated Sunshine Act rules, when a relationship involves a covered drug, device, or biological or medical supply, the name of that product should be recorded. (The proposed definition of covered drug, device, or biological or medical supply is listed in Appendix III). Third, the value of each applicable data element should be recorded. With the variation in standards among organizations regarding monetary thresholds, we propose that a harmonized reporting system prompt reporting individuals to disclose monetary value with sufficient granularity to allow interpretation in accordance with organizational policies. Fourth, to accommodate requests for disclosure over various time frames, each relationship should include a start date and an end date, and archived elements should be easily available. Finally, in the case that a requesting organization is obliged, legally or otherwise, to obtain information in a more detailed or otherwise uniquely categorized manner than is used by the majority of requesting organizations, the harmonized system will accommodate presentation of additional data fields for completion by reporting individuals. (An example is the reporting required of SGEs, who are required by law to report (to FDA or other agencies) certain items such as annuities and trusts, rental income, property, negotiations for employment, and the interests of their employer.)

Goal 2: Harmonized Data Entry, Storage, and Access

The Data Repository and Retrieval Working Group was charged with developing a strategy for the implementation and maintenance of a data repository for secure storage of information and for release of certain elements in response to requests. This task required consideration of several challenges, e.g., data entry and extraction rules, repository characteristics/options, and stewardship/governance. With advances in digital technology and progress in constructing the digital infrastructure in the health field, the technological capacity exists for several approaches. We present below several options for implementation to achieve the goal of harmonization.

Framing Principles

To frame exploration of the options, the working group developed the following core principles for data storage and access.

- Data in the harmonized system are owned by the reporting individual, who fully controls access to and distribution of those data at the time of entry and indefinitely into the future. Note: Once data are reported by individuals to organizations, those reported data are subject to the privacy/confidentiality policies of the organization.

- Security of deposited data is paramount.

- The data storage mechanism should allow the reporting individual to access, update, and save data at any time.

- The data repository or system should include a function to indicate when data are updated and allow for “reminder” prompts for updates.

- Reporting individuals should be able to input data in multiple ways: via a Web-based portal, computer programs, apps, etc.

- The harmonized system should be designed to work with other existing systems, and those not yet developed, to “cross-populate” data among databases, when authorized by individual reporters.

- Requesting organizations should be able to obtain data elements as authorized by reporting individuals.

Data Storage and Maintenance Options

Today, data reported by individuals about their relationships are stored in multiple databases. These databases are locally built and maintained with little ability to interact with each other and with varied levels of security. It is important to emphasize that the data within the harmonized system will be owned and fully controlled by the reporting individual. Although some individuals may be required to share or make public their information, the harmonized system will allow those individuals to report data to the indicated authority rather than facilitating direct public reporting. In the harmonized disclosure system, data might be stored either in a single repository or in multiple locations. Each possibility has benefits and costs which bear exploration.

A centralized data repository is one in which data storage, access, system management, security, and privacy are all managed at a central site. Participants submit data to and request data from this central site. (Definition from the American Health Information Management Association.) The performance of the centralized system depends upon the resources and functioning of the single governing and management entity. Within the framework of agreed-upon standards, a centralized repository uses a single vocabulary and set of definitions which must meet and adapt to the needs of all those who use the system. A centralized system requires an upfront investment in architecture, although this investment may not be substantially different from that of the alternative (a federated system, described below). There are three clear advantages to implementing a centralized system. First, once built, a centralized data repository should be relatively straightforward to manage and operate. Second, a centralized data system can be immediately and fully updated as requirements change. Third, once a link is established with organizations’ systems, it is straightforward to coordinate data transfer from a single data repository to a requesting organization, an important consideration given that a harmonized disclosure system will require multiple, frequent reports. An important consideration with a centralized data repository is the impression that a central database may be less secure or less private. Although the security and privacy of any system require constant, careful stewardship, unfavorable perceptions of a central database containing sensitive information might adversely impact the voluntary participation of individuals or organizations.

A federated data system is an alternative to a centralized data repository. In a federated data system, many different databases are brought together so that data from multiple sources are available through one portal. Under a federated system, data are stored in multiple locations—from individuals’ electronic devices (e.g., computers, tablets) to organizational databases (e.g., universities, journals, specialty societies) to the “cloud.” When a requesting organization wants to receive data from reporting individuals, the appropriate data is supplied to the federated system from its storage locations. A federated system could take advantage of the many data repositories already built and maintained by organizations. Although there are nontrivial maintenance costs associated with these data repositories, it may be sensible to capitalize upon their existence by using a federated data system. A fundamental concern with a federated system is that few databases are currently equipped to meet the needs of groups other than their respective organizations. Given that data will need to flow from reporting individuals to multiple organizations, merely linking current databases without ensuring their interoperability does not guarantee that reporting individuals will be spared the burden of repeated data entry. For the burden to be eased, the architecture of the separate databases must be reconfigured for interoperability and to accommodate single entry of the common elements described in this report.

Whether a centralized or federated database system is used, it is likely that a system that maximizes ease and reduces burden for reporting individuals will include some type of cloud computing mechanism. Cloud computing is “a model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction” (Mell and Grance, 2011). What users of cloud systems appreciate most, though, is the ability for data entered at one site (home computer, work computer, smartphone, tablet, etc.) to be immediately available at all other sites. Although they require intermittent Internet access, cloud applications are superior to Web-based ones in that they do not require continuous access to the Internet.

Data Entry and Retrieval Options

Data Entry

We recommend that individual reporters be presented only with data elements applicable to them, rather than every possible field of entry. To tailor the elements to the reporting individual, data entry should begin with a “mapping” process in which a set of questions determines exactly which data elements the reporting individual needs to provide to comply fully with the requirements of each organization. (Some working group members have likened this process to the initial assessment performed by commercial tax preparation software in which the user fills out a questionnaire to determine the precise tax forms needed.) The mapping process should include at least two steps:

- Identification of positions or roles held by the reporting individual at a particular organization for which reporting is required (e.g., appointment at Duke University, author for the New England Journal of Medicine, board member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology), and

- Determination of whether relationships exist that must be disclosed, per the requirements of those organizations.

The system should allow for updating positions and relationships at any time to accommodate, for example, annual reporting as required by many institutions, as well as periodic reporting such as at the time of publication. The process described will both maximize the efficiency of data entry and help prevent inadvertent omissions. If a reporting individual has no relationships that may constitute a COI under the requirements of his or her positions, the number of data elements to be filled out should be minimal.

Data Retrieval

After data are entered into the system, two approaches are possible for providing the data to requesting organizations: a “push” or a “pull” mechanism. With a “push” mechanism, the reporting individual initiates a data transfer to a requesting organization. The “pull” mechanism allows requesting organizations to query the data repository to retrieve a predefined and preapproved dataset. With appropriate permission structures, the end result of either mechanism is the same—data are shared with requesting organizations with the express permission of the reporting individual. We assume that “push” will be the default position for data sharing from the repository, with “pull” permission granted selectively and specifically by a reporting individual to certain institutions with which he or she has both confidence and common discourse. This duality of intent would be contingent on satisfaction of security safeguards if retrieval access is allowed for multiple requesting organizations. Since data security is of paramount importance, we believe that the optimal system is one in which the individual reporter “pushes” his or her data to requesting institutions.

Operation and Governance of the Harmonized System

Key to the success of a harmonized disclosure system is governance that meets the needs of stakeholders and stewards an easily accessible, continuously updated system. This section lays out the activities that need regular oversight, assessment, and updating; the options for housing and stewardship; and the possibilities for support. Fundamental to these tasks is a “customer”-oriented approach which saves time and adds value for reporting individuals, thereby promoting their voluntary participation in the activity.

Core Capabilities

A number of core capabilities will be required for oversight, assessment, and updating in a harmonized system:

- The system must prioritize data security.

- The system must be built with careful consideration of the optimal system architecture, based on an inventory of existing data warehouses and information systems and a strategy for integration.

- A mechanism must be in place for routine updates of the architecture and data elements as requirements are modified by requesting organizations, rules, and regulations.

- A process must be defined and implemented to ensure the consistency and integrity of data.

- There must be continuous monitoring and maintenance of the system to prevent failures.

- There must be capacity for immediate troubleshooting, including a robust system of “customer service” for reporting individuals and requesting organizations.

- The system must ensure that it meets the needs of stakeholders as they strive to fulfill requirements for disclosure, reporting, and making transparent data about COI.

In addition to these core capabilities, the capacity needed within the system is relatively large. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that in 2010 there were nearly 700,000 physicians and surgeons in the United States (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011). Furthermore, in 2009 U.S. universities alone awarded nearly 20,000 students with PhD degrees in the life sciences (Cyranoski et al., 2011). Assuming half of those with PhDs in the life sciences will be required to disclose relationships annually over the course of a 30-year career, and that all physicians and surgeons will be required to report annually, a reasonable estimate is that the harmonized system will need to manage the data of about 1 million active individual reporters. This needed capacity is likely to increase with the current trend of expanding health professions schools and doctoral programs.

Operations and Oversight

Given the activities required, there are several options for operations and oversight. The executive leadership and administrative function may be developed as a new entity or housed within an existing organization. Creation of a new entity provides the opportunity for de novo formulation of practices and processes; however, the costs of initiation may be high. Developing the activity under the roof of an existing organization allows for building on existing infrastructure, thereby decreasing costs upfront. Over time, a freestanding operation could be established if indicated.

To ensure maximal uptake and representation, either mode of operation should ensure the meaningful participation of stakeholder groups in governance, through the establishment of a governing board and small secretariat comprised of representatives from organizations requiring disclosure and those representing reporting individuals. The purpose of the secretariat would be to ensure that the chosen operating organization has the features and core capabilities described here and continues to meet the needs of stakeholders over time. If housed separately from the organization housing the operating capacity, the secretariat could be funded by a small percentage of the support for the harmonized system, as described in the next section.

Support Options

Bringing together the disparate systems currently in place, maintaining, updating, and improving the system, and meeting the ongoing needs of stakeholders requires initial and ongoing investment. The needs may be met in the context of a for-profit or not-for-profit organization. In either model, several core tenets are likely necessary for a successful business model. First, the products and services offered (the value proposition) should meet the needs of both reporting individuals and requesting organizations. There should be maximal incentives (e.g., friendly interface, clear time savings) and minimal costs to participation for reporting individuals. Incentives for requesting organizations are also needed (e.g., easy, timely access to data and reports) and their costs of participation must not exceed those currently incurred. The revenue stream for the harmonized system might flow from several sources: grants from interested organizations and/or philanthropies, membership dues, subscription fees, licensing, or a hybrid of multiple sources.

An example of a support option that takes into account the requirements above is a tiered subscription model in which reporting individuals and requesting organizations pay use- or feature-based fees to the harmonized system. For individuals, such a system might bear some resemblance to personal tax software packages in which the product fee is determined by the complexity of the individual’s tax needs. One major company offers a free option for completion of the federal 1040EZ form and other simple federal tax returns. The company then offers more robust packages for standard individual tax returns ($35), increased capacity to detect tax deduction opportunities ($50), inclusion of investments and rental property ($75), and home business needs ($100). Such a model might be created for the harmonized system in which an individual’s fee would be calculated based on complexity of reporting needs. For organizations, a similar model could be constructed based on the type of organization (academic institution, CME provider, journal) and use of system (e.g., number of individual records requested).

Existing Resources

A number of organizations currently maintain (or are developing maintenance capacity for) data housing and retrieval that might serve as models for, or perhaps operators of, a nationally harmonized COI reporting repository. Organizations with potential capacity and ability to support the harmonized system are listed in Appendix IV. We note that although extensive technical capability exists, none of the systems described is configured currently to meet all core capabilities or address all audiences needed for a harmonized system of disclosure. We present them as a sample from the field to inform recommendations.

Proposal for Structure and Support

A group of stakeholders met in June 2012 to discuss the options for structure, processes, and governance investigated and outlined above. Participants at the meeting indicated the centrality of this work to easing the burden of reporting relationships that may constitute COI and underscored the importance of instituting a national system to harmonize disclosure. Accordingly, we propose the following structure and support for the system:

- Data repository: centralized. We believe that a centralized database holds the greatest potential for efficiency and cost savings. Many organizations currently invest in the maintenance of complex data and human systems which require expensive upkeep. While a harmonized system will not eliminate the need for organizations to maintain a database to receive and filter information from the harmonized system, we anticipate that the remaining intra-organizational database will be significantly smaller and less resource-intensive to maintain. We assume that “push” will be the default position for data sharing from the repository, with “pull” permission granted selectively and specifically by a reporting individual to certain institutions, if satisfaction of security safeguards can be assured.

- Business model: not-for-profit. To streamline discussions of financial considerations in these early stages, we suggest that the harmonized system be established as a not-forprofit model at the outset.

- Revenue generation: subscription or membership. Anticipating that the activity will offset to some extent organizations’ current costs, we propose a subscription or membership model—tiered based on size, utilization patterns, or other parameters of participating individuals and organizations—for revenue generation.

- Housing structures: operations and governance. Housing the operations within an existing organization may maximize resources; however, collective establishment of a new organization is a viable alternative if institutions with experience and resources in managing similar data systems are willing to contribute these to the new organization.

We will establish a steering group comprised of equal representation from requesting and reporting organizations, as well as those with technical expertise necessary for carrying out design and implementation of the harmonized system. Key tasks of the steering group will include evaluating existing organization, support, and governance options, establishing a secretariat, and moving forward with implementation. The IOM has agreed to organize and host the initial gatherings of the steering group.

Appendix I – Working Groups

Field Definition Working Group

Task: Identify and define the fields of entry needed for individual scientific authorities (e.g., researchers, authors, reviewers, expert advisers, students, trainees) to accommodate most current and anticipated requirements (including all anticipated under federal regulations); propose process for stewardship/revision.

Participants: Allen Lichter (Chair) (American Society of Clinical Oncology), Timothy Anderson (American Medical Student Association), Niall Brennan (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services), Eric Campbell (Mongan Institute for Health Policy), Susan Chimonas (Columbia University), Guy Chisolm (Cleveland Clinic), Christopher Clark and Susan Ehringhaus (Partners HealthCare), Allan Coukell (The Pew Charitable Trusts), Phil Fontanarosa (JAMA), Ray Hutchinson (University of Michigan), Norm Kahn (Council of Medical Specialty Societies), Christine Laine (American College of Physicians/International Committee of Medical Journal Editors), Lorna Lynn (American Board of Internal Medicine), Jill Warner (Food and Drug Administration), Dorit Zuk (National Institutes of Health), Adam C. Berger (IOM Staff)

Data Repository and Retrieval Working Group

Task: Develop strategy for implementation and maintenance of database—e.g. data entry and extraction rules, repository characteristics/options, stewardship/governance

Participants: Ross McKinney (Chair) (Duke University), Erica Breese (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services), Niall Brennan (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services), David Butler (Consumers Union), Milton Corn (National Library of Medicine), Diane Dean (National Institutes of Health), Jeffrey Francer (PhRMA), Mark Frankel (American Association for the Advancement of Science), Timothy Jost (Washington & Lee University), Mary LaLonde (Partners HealthCare), Patrick McCormick (Neurosurgical Network, Inc.), Pamela Miller (New England Journal of Medicine), Heather Pierce (Association of American Medical Colleges), Paul Weber (Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions), Isabelle Von Kohorn (IOM Staff)

Appendix II – Definitions

Noted below are definitions proposed by the Field Definitions Working Group for the terms in Table 1. They are drawn from documents developed by the NIH, FDA, CMS, ICMJE, various universities, and English-language dictionaries.

Award: A prize or other symbol of recognition given for an achievement or based on merit.

Bond: A debt security in which there is a formal contract to repay borrowed money with interest at fixed intervals.

Carried interest: A distributive share of partnership profits in excess of the partner’s relative capital contribution.

Consulting fee: Payment received for the provision of personal services, not as an employee, that require advanced knowledge and expertise in a field of science or learning, including the rendering of advice or consultation. Includes fees for services provided as a member of a scientific advisory board, an agent of a company (e.g., someone who receives a commission or finder’s fee).

Convertible security: A security that can be converted into a different security, typically shares of a corporation’s common stock.

Dividend: A portion of a company’s profit that is distributed to shareholders proportionally based on ownership.

Expert witness fee: Payment for serving as an individual qualified to speak authoritatively by virtue of his or her special education, training, knowledge, skill, or experience/familiarity, or payment for providing expert advice related to a scientific, technical, or professional matter. Expert witness services include providing a written report, appearing for a deposition, or otherwise providing information, including testifying under oath.

Faculty or speaker fee: Compensation for speaking to others to impart knowledge or skills in health care and life sciences, including, for example, continuing education, board review, seminars, lectures, teaching engagements, speakers bureau or other fees. [Note: the Sunshine Act proposes to define “direct compensation for serving as faculty or as a speaker for a medical education program” as “all instances in which applicable manufacturers pay physicians to serve as speakers, and not just those situations involving ‘medical education programs.’” As noted, comments were invited in this area and clarification is expected in the final rule. Of note, the proposed rule does not provide guidance about where other faculty fees (such as curriculum development or online courses) should be recorded.]

Fiduciary fee: Payment for serving as a person with the duty to act legally on behalf of another person or entity, typically ensuring the financial well-being of that person or entity (e.g., as a board member, trustee, governor, manager, executive).

Founder: An individual who has founded or established an organization or company.

Gifts: A transfer of tangible or intangible value for which the recipient does not provide equal or greater consideration in return. [Note: Final definitions should follow those in the Sunshine Act final rule (e.g., food gifts).]

Grant: A financial transfer of money, property, or both to an entity to carry out an approved project or activity.

Honoraria: Payments to a professional person for services for which fees are not legally or traditionally required (e.g, an appearance, speech, article). [Note: the Sunshine Act proposed rule requests comments on the distinction between honoraria and direct compensation for serving as a CME faculty or speaker. The definition of these two items should correspond to the final rule.]

License fee: Payment to the holder of a patent or a copyright for a limited right to reproduce, sell, or distribute the patented or copyrighted item. Includes one-time, scheduled, or milestone payments.

Limited liability company membership: Participation as a stakeholder in a business entity that has certain characteristics of both a corporation and a partnership or sole proprietorship.

Loan: The receipt of money or other things of value, for which a repayment agreement is in place.

Manuscript fee: Compensation received for authorship, editing, reviewing, or other services associated with preparing of materials for publication.

Officer fee: Payment for providing an institution, company, or organization with executive leadership or management.

Partnership: A business arrangement in which ownership and obligations are shared among two or more individuals.

Review activity fee: Compensation received for professional review of scientific activities, including participation on a data-monitoring board, statistical analysis, etc.

Royalty: Compensation for the use of property, usually copyrighted works, patented inventions, or natural resources, expressed as a percentage of receipts from using the property or as a payment for each unit produced.

Salary: Fixed compensation paid regularly for services rendered as an employee.

Stock option: The right to purchase stock in the future at a price set at the time the option is granted (by sale or as compensation).

Stock: Also known as corporate stock, equity, or equity securities, instrument (share certificate or stock certificate) that entitles holders (shareholders) to an ownership interest (equity) in a corporation and represents a proportional claim on its assets and profits.

Appendix III – A Harmonized System and the Physician Payment Sunshine Act

This table presents the broad categories of data elements expected to be included in the harmonized system. The table attempts to make clear the intended one-to-one correspondence with anticipated categories required by the Sunshine Act. This table must be updated upon enactment of the final rule by CMS and updated periodically as indicated by future legislation and rule making. This type of table may be constructed to ensure direct correspondence to any requesting organization.

It is important to note that the harmonized reporting system must be able to identify and highlight those relationships among reporting individuals and manufacturers that are applicable. The Sunshine Act applies only to a subset of manufacturers and products. The law and proposed rule provide definitions identifying relevant manufacturers and products are as follows:

- Applicable manufacturers are entities “(1) engaged in the production, preparation, propagation, compounding, or conversion of a covered drug, device, biological, or medical supply for sale or distribution in the United States, or in a territory, possession, or commonwealth of the United States; or (2) Under common ownership with an entity in paragraph (1) of this definition, which provides assistance or support to such entity with respect to the production, preparation, propagation, compounding, conversion, marketing, promotion, sale, or distribution of a covered drug, device, biological, or medical supply for sale or distribution in the United States, or in a territory, possession, or commonwealth of the United States.”

- A covered drug, device, biological, or medical supply is “any drug, device, biological, or medical supply for which payment is available under Title XVIII of the Act or under a State plan under Title XIX or XXI (or a waiver of such plan), either separately, as part of a fee schedule payment, or as part of a composite payment rate…With respect to a drug or biological, this definition is limited to those drug and biological products that, by law, require a prescription to be dispensed. With respect to a device or medical supply, this definition is limited to those devices…that, by law, require premarket approval by or premarket notification to the Food and Drug Administration.”

Of note, all manufacturers who meet the definition of an applicable manufacturer must report payments related to all their products. We anticipate that these definitions may be altered in the final rule. Regardless, once the final rule is available, it will be incumbent upon the operators of the harmonized system of disclosure to maintain the capacity within the system to identify and flag relationships and covered drugs, devices, biologicals, or medical supplies that fall under CMS regulation and may be subject to review and appeal.

General Notes

- Date of payment. If an arrangement involves payment over time, the manufacturer will elect whether to report a single line-item payment on the first day of payment or report each payment separately. We recommend that manufacturers relay their accounting plan to reporting individuals. Alternatively, the reporting individual should record each payment separately and the harmonized system should have the capacity to filter and aggregate these payments.

- Associated covered drug, device, biological or medical supply. The proposed rule states that “in cases when a payment or other transfer of value is reasonably associated with a specific drug, device, biological, or medical supply, the name of the specific product must be reported.”

- Form of payment and nature of payment. In accordance with the legislation, CMS indicates that for each transaction, both form and nature of payment must be reported. To maximize the utility of reporting, CMS proposes that the categories within both form of payment and nature of payment be distinct. They provide an example: “If a physician received meals and travel in association with a consulting fee, we propose that each segregable payment be reported separately in the appropriate category. The applicable manufacturer would have to report three separate line items, one for consulting fees, one for meals and one for travel. The amount of the payment would be based on the amount of the consulting fee, and the payments for the meals and travel. For these lump sum payments or other transfers of value, we propose that the applicable manufacturer break out the disparate aspects of the payment that fall into multiple categories for both form of payment and nature of payment.” (Proposed rule, pp. 23-24.)

- Physician ownership. Manufacturers must report ownership and investment interests of physicians and their “immediate family members.” The proposed rule states that ownership or investment interest “may be direct or indirect, and through debt, equity, or other means. Ownership or investment interest includes, but is not limited to, stock, stock options (other than those received as compensation, until they are exercised), partnership shares, limited liability company memberships, as well as loans, bonds, or other financial instruments that are secured with an entity’s property or revenue or a portion of that property of revenue. As required by statute, an ownership or investment interest shall not include an ownership or investment interest in a publicly-traded security or mutual fund.”

Appendix IV – Existing Resources

Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID)

http://orcid.org

ORCID’s mission is to “solve the author/contributor name ambiguity problem in scholarly communications by creating a central registry of unique identifiers for individual researchers and an open and transparent linking mechanism between ORCID and other current author ID schemes. These identifiers, and the relationships among them, can be linked to the researcher’s output to enhance the scientific discovery process and to improve the efficiency of research funding and collaboration within the research community.” ORCID, Inc., is a nonprofit organization incorporated by members of the global scholarly research community and managed by a board of directors drawn from among sponsoring stakeholders. Daily operations of the organization are run by staff. The business model and technical structure are under development.

eFolio Connector

https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/october2011/262444/efolio-connector.html

The vision for the eFolio was developed at a 2007 conference convened by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the Federation of State Medical Boards, and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME), supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The eFolio is envisioned as a tool to connect organizations that assess and license physicians with the goal of creating “a shared infrastructure that will enable students and physicians to view their educational and professional data.” The eFolio Advisory Group—a group of medical educators—helps guide the project which is being developed by AAMC and NBME.

The National Disclosure System

https://nationaldisclosuresystem.org/

The Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions is developing an online uniform disclosure system and central repository. The purpose of the system is to “provide faculty from all healthcare-related professions (CME, CPD, CE), as well as CE planners, with the ability to enter their disclosure/COI information online in a secure centralized database, for all educational activities in which they participate.” The technical details and business model are under development.

ClinicalTrials.gov

http://clinicaltrials.gov

ClinicalTrials.gov was initiated in 1997 and expanded in 2007. Its goal is to provide “patients, family members, health care professionals, and other members of the public easy access to information on clinical studies on a wide range of diseases and conditions. Information is provided and updated by the sponsor or principal investigator of the clinical study and the web site is maintained by the U.S. National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health.”

References

- Blumenthal, D. 1996. Ethics issues in academic-industry relationships in the life sciences: The continuing debate. Academic Medicine 71:1291-1296. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199612000-00010

- Bodenheimer, T. 2000. Uneasy alliance-clinical investigators and the pharmaceutical industry. New England Journal of Medicine 342:1621-1626. https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJM200005183422024

- Cho, M. K., R. Shohara, A. Schissel, and D. Rennie. 2000. Policies on faculty conflicts of interest at US universities. JAMA 284:2203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.17.2203

- CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2011. Proposed rule: Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests.

http://federalregister.gov/a/2011-32244 (accessed May 22, 2012). - Common Application. 2011. Mission. https://www.commonapp.org/CommonApp/Mission.aspx (accessed May 22, 2012).

- Cyranoski, D., N. Gilbert, H. Ledford, A. Nayar, and M. Yahia. 2011. Education: The PhD factory. Nature 472:276-279. https://doi.org/10.1038/472276a

- ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors). 2009. Ethical considerations in the conduct and reporting of research: Conflicts of interest. http://www.icmje.org/ethical_4conflicts.html (accessed May 22, 2012).

- Institute of Medicine. 2009. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12598.

- Leshner, A. I. 2011. Rethinking the science system. Science 334:6057. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1215299

- NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2011. Financial conflict of interest. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/coi/index.htm (accessed May 22, 2012).

- Mell, P. and T. Grance. 2011. The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Available at: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-145/final (accessed January 28, 2020).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2011. Occupational employment statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm (accessed January 28, 2020).